|

|

Sixty-two people died and 1,400 homes and buildings were burnt in bushfires in southern Tasmania on 7 February 1967, a day that’s now widely known as ‘Black Tuesday.’ At the time, it was Australia’s second-worst bushfire disaster in terms of loss of life (nearly fifty years later it ranks as Australia fourth-worst bushfire). My parents lost their house, car and all their possessions on Black Tuesday; and this account of the fires by my father is an edited extract from his unpublished memoirs that has been supplemented by material in two long letters that he wrote a week after the disaster caused by a conflagration of 110 fires within a 35-mile / 56-kilometre radius of Hobart.

Introduction

The spring and early summer of 1966 were very wet in Tasmania, and as a result there was a luxurious growth of all plant life. It continued to rain nearly every day until Christmas, but after that we had no rain for about six weeks. The consequence was that all the abundant growth was dry and very flammable. January and February 1967 were hot, and it was generally realised that the likelihood of outbreaks of bushfires was very real. There was a drive to enlist all able-bodied males in rural and semi-rural areas as volunteer fire-fighters. I put my name down and even attended a dinner for the volunteers at the pub in Fern Tree. As I came out from the dinner to return home to Westringa Road, several of us saw a fire in the bush above the road and we stopped a drunken lout who was deliberately lighting fires. He was put into a car, driven six miles / 10 kilometres down to the main police station, and handed over to the police. They seemed remarkably unwilling to do anything about it, and apparently all that happened to the man was to be told to be a good boy and sent home.

Tuesday morning, 7 February 1967

About a fortnight later, early on Tuesday morning, 7 February 1967, Lilian got up sometime around 3:00 am and looked out of the window at a red glow south down the road to Huonville: no flames were visible, just smoke over the hill with a red glow. At about 6:30 am the Fern Tree fire siren sounded, so – knowing there was only one operation booked for the whole Hospital in the morning – I phoned Bill Thompson and said I wasn’t coming in, and Charles and I decided to obey the summons.

Stuart (then aged 20) was away working as student casual labour helping in the canteen of an army camp at Fort Direction, near South Arm at the extreme end of the left bank of the Derwent estuary about 9 miles / 15 kilometres as the crow flies from our house in Fern Tree but almost 30 miles / 50 kilometres by road, while Nigel and Heather were arriving in Adelaide, their first port of call on their voyage to England on the M.S. Aurelia. Charles – still not yet sixteen – was a pupil at The Friends School, and 7 February was the last day of the summer holidays. Linda, also a Friends student, had arranged to spend the day at one of the beaches with a school friend, so Charles and I set out together. We were picked up by trucks and taken to various places where the fire was raging.

This comparatively rare 1967 colour photograph is of a burnt-out house in Pillinger Drive, Fern Tree,

which is about one-and-a-quarter miles / two kilometres from the house where my parents and

siblings lived in Westringa Road, Fern Tree. (This photograph was taken by Jack Weatherill,

and permission to reproduce it was kindly given to me by his grandson, Ben Short.)

We both spent a very busy morning beating out flames and carrying five-gallon / 23-litre drums on our backs to spray water on the fires. I got separated from Charles by about 8:00 am. Charles later said that he will never forget seeing the fires being spread by rabbits that were literally on fire: the faster they ran, the more fires they spread! Charles was also impressed by Salvation Army members who were there – in their church uniforms – handing out cups of tea and cucumber sandwiches to the fire-fighters. I was fire-fighting mainly at the Neika Post Office and a bit further on near the lovely home of the Hobart architect, Mr Lighton. It was terribly hot, windy and smoky. I got very tired and sweaty, and had sore eyes.

Black Tuesday afternoon

About 2:00 pm I thought I had better go home and ring the Hospital to see if they wanted me. They said it wasn’t urgent but they were getting a few burns cases in from the Richmond / Colebrook area and perhaps I’d better be on hand. So I sprayed the outside of the house with a hose, changed, and asked Lilian for something to eat. Then the power went off, so the last meal I had in Westringa Road was a glass of milk. We did not have any candles, and it was so dark that I could not see the colour of the tie I was putting on, nor did I have enough light to shave. Out on the lawn Lilian looked as if she was going to be blown away by the gale force gusts. I tried to ring the Hospital again to say I thought I ought to stay with Lilian unless they really needed me, but the line was out of order. So Lilian said I should go to the Hospital and she would come with me as far as the Fern Tree shop in order to get some candles and then walk back home.

As I had not shaved early in the morning before going out fire-fighting and hadn’t been able to shave at home, I decided to take my electric razor with me to the Hospital and, finding the glove box full of maps etc., I put it under the seat of the car. I dropped Lilian at the store and continued down the road to Hobart but did not get very far because there was a policeman stopping all traffic. I tried to pull rank and explain that I was in charge of anaesthetics at the Hospital and that therefore he had better let me through. I learnt then that it was not just a matter of a police ruling, but a physical impossibility to drive down the road as the fire had burnt away the wooden poles carrying the power lines and telephone wires, and the road was impassable because of the tangled wires and other debris across it. So I returned to the Fern Tree village store. Lilian had bought her candles and was chatting to other Fern Tree inhabitants where all sorts of rumours about the extent of the fire were circulating. I used the Post Office phone to let the Hospital know I was cut off, and we decided to go back home.

This photograph, taken by an unknown photographer shortly after the Black Tuesday bushfires, is

of abandoned and burnt-out cars standing near the remains of the Fern Tree hotel. (Permission

to use this copyright picture was given to me by the National Library of Australia.)

At the top of Westringa Road, a Hobart City Council truck stopped us and asked where an old lady of 91 lived: they had been told to take her out of her house as there were fears for her safety. I told the men to leave their truck at the junction of Westringa Road and Huon Road as the road deteriorated past our house and became just a track. We then took one of the men down to the farm to look for the woman (who was the mother-in-law of Mr Gray, the farmer). Lilian ran down into the farm and found the door wide open, but the house was absolutely empty of people.

When we returned the few hundred yards back to our house, we saw that a fire had started at the bottom of the ravine that carried a small stream, Fork Creek, along the boundary of our land. I backed the car into our concrete drive (for a quick getaway). We stopped the car. We wanted to go and try to save something from the house, but also realised that we would not be able to save the house with a small garden hose if the fire continued to spread in our direction. As I got out of the car, the fire reached the lip of the gully on the edge of our cultivated garden area, and the trees below the lawn literally burst into flames – like a torch! There was then no time to save anything.

The remains of Bobby and Lilian Roberts’ home at 8 Westringa Road, Fern Tree. (This photograph

was taken approximately two months after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

Burnt trees at 8 Westringa Road, Fern Tree. The large black stump in the centre of the picture used to

be the family’s chopping block where wood was split for the living-room fireplace. (This photograph

was taken approximately two months after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

The remains of the house that had belonged to the Bax family, my parents’ Westringa Road neigh-

bours. Rubble hadn’t been moved from the property because the Baxes moved to Queensland

after the 7 February 1967 fires. (This photograph was taken approximately two months after

the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

Fire on all fronts

Lilian said we had to leave immediately in case the lawn caught fire and the engine stalled. We drove back to the small open area opposite the pub, where there were about 70 cars and two- to three-hundred people, all herded like sheep. Every road was cut – you couldn’t go down to Hobart, couldn’t go up the mountain, couldn’t go down Summerleas Road, and couldn’t go back to Huonville. So we just waited, getting more and more frightened and crowded. Babies and children were crying; men and women were getting nervy and panicky. A policeman was there, shepherding people into the open area, but there were also a lot of cars, including ours. I pointed out to the policeman that if the fire was going to reach us, we would be at a great risk of the fuel tanks exploding. He agreed and ordered everybody to move their cars away from the open area. I took mine some way back along Huon Road.

Eventually we could see fire, and smell it, and hear it approaching on three fronts – from behind the hotel, down the mountain, and along the road in the direction of our house. I found a bucket and filled it with water, and Lilian and I soaked our clothes in it. Lilian took off her frock and dipped it in the bucket, and I did the same with my blazer. Then Lilian and I went to sit in our car – parked right up against the bank, under a cutting on the mountain side of the road – hoping that with the windows shut we could keep sparks and smoke out, and that the fire would blow over the top of us without either cooking us or exploding our petrol tank.

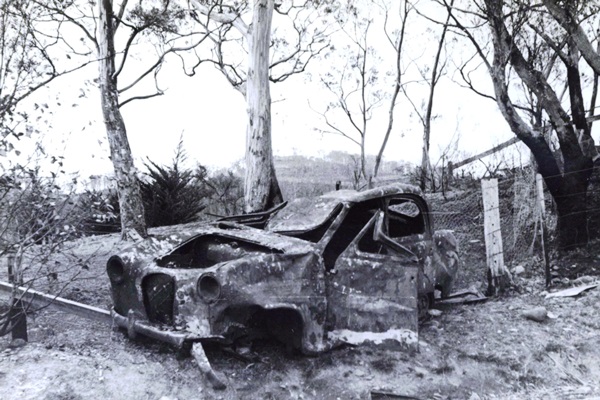

A car in Free Tree that burnt and exploded during the 7 February 1967 bushfires. (This photograph

was taken approximately two months after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

Another car came and parked on the other side of the road where the land fell away steeply in what I would have thought was a dangerously exposed position because the flames from any burning trees on that side would come up and lick the sides of the car. As it turned out that is exactly what did happen and that car's petrol tank exploded. Lilian exclaimed that she was not going to sit in the car waiting to be burnt and jumped out and started to run back to the village centre. I abandoned the car and ran with her through falling red hot ash and burning bark, leaves and twigs. Small branches from the roadside trees were falling all around us, but we reached the Fern Tree pub unharmed. We went and stood in the bus shelter opposite the pub, where there were about 30 people. In the event it did not get burnt, but the smoke was terrible and everyone was scared stiff. By now the fire was very visible. Beyond the pub across the road, we could already see several houses well ablaze.

The site of the former Fern Tree pub. (This photograph was taken approximately two months

after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

Escape

Just when we thought all hope had gone, the policeman in charge announced that the road down to Hobart was now passable and suggested that everybody should escape that way as quickly as possible. I ran back towards the car but the heat was too intense to get through, so I returned and shortly after that a lorry came along and we jumped on board and headed for the city.

The 7 February 1967 bushfires spread down hillsides and valleys into Hobart, reaching as close as

one-and-a-quarter miles / two kilometres to the city centre. This colour photograph was taken by

Colin Woolford, and looks down onto and across South Hobart. The remains of the Cascade

Brewery can be seen near the centre of the picture.

We arrived at the Hospital where I found that they were soon to start treating casualties from the fire, so I got to work immediately while someone took care of Lilian and took off her soaking clothes and dressed her in a theatre gown. One of the honorary anaesthetists, Alan Bond, who had come in to help, took her to his home in Battery Point, the nearest inner suburb, and left her with his wife, Jenny, who was an eye surgeon. Jenny gave her a meal and then Lilian tried to repair the damage I had done to her hairdo by soaking her with water: ‘Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.'

Charles was given a lift from the fire on another lorry and asked to be dropped off at Westringa Road and was appalled to find that not one house was left standing in the road, all were smoking ruins with just a brick chimney and fireplace to mark the spot. He picked up a stray dog that he found running around, obviously a fire victim, and the lorry then brought its load down to Hobart.

My youngest brother Charles and Stuart's dog, Elsa, survey the ruins of the Fern Tree

store. (This photograph was taken approximately two months after the Black Tuesday

fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

Shortly after Huon Road becomes the upper end of Davey Street, they passed the home of Harry Jones, an Ear, Nose and Throat surgeon, and his wife Betty, who were standing watching the cars returning from the smouldering countryside. They recognised Charles and took him and the dog in for the night. They were able to tell him that Lilian and I were safe and where we were. Later during the evening, Linda and her school friend returned to the city after spending the last day of their holidays at the beach and then playing softball. She tried to catch the next bus up to Fern Tree only to be told more or less that Fern Tree was no longer. The poor child was naturally very upset, but had the good sense to come to the Hospital to find out what had happened to us and she appeared in the operating theatre area and was relieved to see me alive. Her school friend's parents took her home with them for the night until we could sort out what we would do.

Reminiscent of the blitz

I was kept busy from 5:00 pm until near midnight treating 33 patients admitted with burns severe enough to warrant hospitalisation. The scene in the operating theatre suite was for me very reminiscent of the days of the blitz in London during 1940-41. One similarity was the rapid turn over of cases, and another was the dirty state of the patients, nearly all of them were blackened with smoke and wood ash whereas during the blitz it had been house rubble and broken glass.

As none of the patients could be assumed to have empty stomachs, we had to avoid giving complete general anaesthesia. I had been doing some work on the use of a combination of neuroleptic and analgesic drugs, known as neuroleptanalgesia. Neuroleptic drugs do not, in the doses used, cause unconsciousness but produce a state of mental detachment, and when given with strong pain-killers known as analgesics, cause the patient not to worry about what is happening to them and yet be awake enough to talk and to respond to questions or orders. Thirty-one of the thirty-three patients that evening were given neuroleptanalgesia.

Murray Drew was the surgeon in charge of the Burns Unit at the Royal Hobart Hospital, and several of the honorary surgeons turned up to help so that we were able, by using two surgeons to each table, to get through the work without it dragging on well into the night when doctors and nursing staff would be tired and also making sure that the patients at the end of the list were not kept waiting unduly for treatment.

We were very pleased with the efficacy of the neuroleptanalgesia. Just how efficient it was is demonstrated by the following two incidents. I was at one table with Murray Drew operating on a man who was very severely burnt over 90% of the body surface. Murray had just started pulling off the dead skin when the orthopaedic surgeon, David Roebuck, put his head round the door of the theatre and asked if he could be of help. Murray asked him to scrub up and come and work simultaneously on the other side of the patient. Roebuck did not know I was using this new technique and assumed that the patient was asleep so he was uninhibited in telling us some funny story. When he delivered the punch line he was astonished when the patient joined in the laughter. The other occasion proving the effectiveness of the analgesia was when Murray was performing debridement of the whole of the back area of a man who lived at Fern Tree and was incidentally the father of one of the nursing sisters. Murray knew the man and was chaffing him about being burnt on the back saying that he was surprised that for an experienced bush man he had been running away from the fire. The patient replied 'Well, the fire kept changing direction and didn't give any hand signals either!', demonstrating that he had so little discomfort that he was able to joke about it.

When all the patients had been dealt with I, too, went off to Alan Bond's house for the night. The next day we started to receive donations of clothing which were absolutely essential as even the clothes we had worn on the day were so ruined by soaking from my bucket, smoke and burnt debris that they were deemed uncleanable. Bill Law lent us his car for three days, and then the Department of Health Services lent us a Valiant, which went beautifully … except for an intermittent fault of refusing to start at all on the self-starter.

Surveying the damage

On Saturday, 11 February, we decided to go and have a look at the remains of our property in Westringa Road. Everything was razed to the ground except the brick chimney stack and that proved to be a common sight: lonely chimney stacks surrounded by black ash.

‘Lonely chimney stacks surrounded by black ash.’ (This photograph was taken approximately

two months after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

From the site of the chimney I was able to determine just where a chest of drawers had stood in our bedroom and we fossicked about looking for anything worth salvaging. We found a collection of South African tercentenary crowns that I had, a Dutch two-and-a-half guilder piece, and a Kennedy half-dollar, but only skeletons of cameras, binoculars, transistors, TV sets, radiograms, and the like. I had kept the coins in a plastic bag in the top drawer of the chest of drawers and there they were, blackened and tarnished by the heat and smoke but still recognisable for what they were. Next to the telephone we kept a child's money box in the forlorn hope that any of our children making a personal call would make a contribution. We found all those pennies welded together almost exactly in the shape of a map of England, Scotland and Wales. Charles souvenired this (but sadly no longer has it).

We also found some little china plaques that had been on some Wedgewood pottery, still quite intact after their ordeal by fire. Diana Hargrave-Wilson who knew the Wedgewood family suggested that I should write to the firm in England and tell them, so we did and eventually we received a copy of one of their staff journals with a little write-up about it and also a new Wedgewood teapot with the compliments of the management.

Stuart found our cat alive the day after the fire, and two chickens. The cat went to live with Stuart’s young long-haired law lecturer, Mr Raeburn. On the Saturday, we managed to catch Linda’s horse, Princess, also miraculously quite unhurt but very frightened, and took her up to the brother of Mr Gray the farmer, in one of the houses in Grays Road (the road opposite Westringa Road), which mostly survived. Because Mr Gray’s farmhouse had been burnt down and his grass was all burnt, there was no food there for Princess, and because the farm’s water had been cut off, there was also nothing at the farm for Princess to drink.

A picture taken from Westringa Road, Fern Tree, looking up towards houses in Huon Road and

Grays Road that somehow survived the 7 February 1967 bushfires. (This photograph was taken

approximately two months after the Black Tuesday fires by my brother, Stuart Roberts.)

We explored along Huon Road and found our car. The back part had been burnt but the front was apparently untouched and I looked inside and saw that some looter had already been at work removing the car radio, but he missed my electric razor which I had slipped under the front seat. I reported the theft of the radio and had high hopes of it being returned as it was a South African make and therefore scarce in Australia, but what would make it unique was the fact that accidentally the small plaque with the brand name on it had been put on upside down at the factory. However it was not to be: once more the saying 'Crime does not pay' was disproved: callous looters who could stoop to robbing people who had just lost their home and contents got off, not only scot free, but richer. Looters in times of national disaster should be dealt with much more strictly.

Everyone was very kind

In the immediate aftermath of the fires, everyone was very kind. I took several sets of trousers donated by doctor friends to be altered, and the tailor I took them to refused to charge me for them. The Sherreys, Laws, Hurburghs, Chestermans, Jones, Kirklands, Woods, Borehams, etc., etc. – to name only a few – were wonderful to us. We were hardly allowed to stay at 'home' to eat the food they brought us. During the first week alone after the fires, we went to dinner with the Kirklands, Woods, Kellys, and Merediths, and we had Sunday lunch with the Sherreys. We had cables or letters from the Hammerschlags, Gerrards, and Littles in Australia; from the Kratzers and Selverstones in the USA; from Mme Rainier in France; from the Knights and Gregorys in Johannesburg; from the Dusseks, Gardners, Caswells, Hewers, and others in England; as well as from the Lichters in New Zealand – he used to be in Johannesburg and was a chest surgeon in Dunedin.

Colin Munro and his wife, Anna, had a house in Sandy Bay where they had built a 'granny flat' under their living area and he offered it to us as a temporary refuge. Space there was limited so we were only able to take it for Linda, Lilian and myself. It was very comfortable indeed – for two – but as we had Linda with us sleeping on a stretcher in the living room, she had to go through our bedroom to the bathroom and we had to go through hers to the front door, but one must admit they were minor inconveniences for refugees! Stuart and Charles were taken in by the parents of some of their friends: by the Elthams and the Rusts respectively.

Friends and relations were wonderful in their response to the situation. Many friends in South Africa even sent the maximum amount that their strict currency export regulations would allow. Lilian's sister in America, Gladys (namely, Bobbie Selverstone) showed the most acute understanding of our needs by sending a cabin trunk filled with household linen and spare clothing and most importantly any old photographs she had of our family, realising that whereas most things can be replaced by paying for them, intimate items of sentimental value only, such as family photographs, can never be replaced.

My insurance company also treated me kindly over the car. They called the car a complete write-off and so enabled me to buy a replacement immediately instead of being without a car for weeks while the very extensive repairs that would have been necessary were carried out. John Sherrey, the Ear, Nose and Throat surgeon, kindly decided that he needed a new car and let me buy his old one instead of trading it in.

Less than a week after the fire, Athol and Beryl Corney, who had been Jim Kratzer's AFS host parents, suggested that we might like to look after Beryl's mother's house in Glenorchy. Mrs. Langham was a keen amateur orchid grower and so was her sister in Sydney and she decided that it was time she paid her sister a long visit. We were offered the house rent-free on condition that we looked after not only her orchids but also her small dog. Although the offer was tempting, I wasn’t initially very keen on moving out north: we knew no-one on that that side of the city except for the Merediths, the Jamisons and the Corneys. Most of our friends were in the Sandy Bay, Battery Point, South Hobart area. However, it meant that we were able to get together again as a family while we looked for a more permanent arrangement. Despite the fact that Glenorchy was not the most convenient location from which we could go about our various vocations – the Hospital for me, school for Charles and Linda, and University for Stuart – we were very thankful for this temporary alleviation of our residential problem.

It was Charles who found us our next home, a lovely old solid brick house with a slate roof in a large garden in Bishop Street in New Town, one of the oldest suburbs just to the north of Hobart’s city-centre.

10 Bishop Street, New Town: the house that Bobby and Lilian Roberts bought in Hobart

after the Black Tuesday bushfires. They lived in it from 1967 until 1971.

We were now able to settle down to a normal family life after the upheaval of the bushfire, and we lived in that house for nearly four years, longer than anywhere else in Tasmania till then.

Personal postscript

As my father noted in his description of the Tuesday, 7 February 1967, Tasmania bushfires, 'Nigel and Heather were arriving in Adelaide, their first port of call on their voyage to England on the M.S. Aurelia.' Heather and I spent the day ashore visiting a friend, Alison McMichael, completely unaware of the devastation that was occurring in Hobart, which we’d left only a few days beforehand.

A picture of the M.S. Aurelia. (I would like to thank Reuben Goossens and his maritime history web-

site, ssMaritime, for originally scanning this picture from a Cogedar Line promotional photograph.)

Late on the Tuesday afternoon, as the ship was leaving Port Adelaide, I went up onto the main deck and sidled up alongside a man who had a transistor radio and was listening to the 6:00 pm ABC news (I wanted to hear whether Gough Whitlam had replaced Arthur Calwell as leader of the Australian Labor Party). There was a very brief mention on the news of fires in southern Tasmania, but it didn’t sound as though anything especially abnormal had happened, and neither Heather nor I gave the matter any further thought either that day or the next (when we heard nothing whatsoever about the fires).

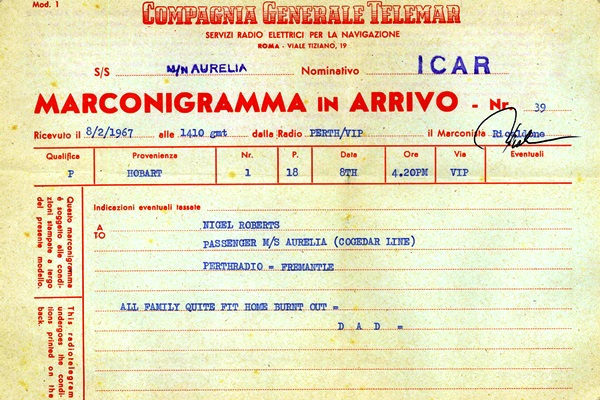

We were just getting ready to leave our tiny cabin deep down in the bowels of the ship to go to breakfast on Thursday morning, 9 February, when the following telegram was pushed under our door:

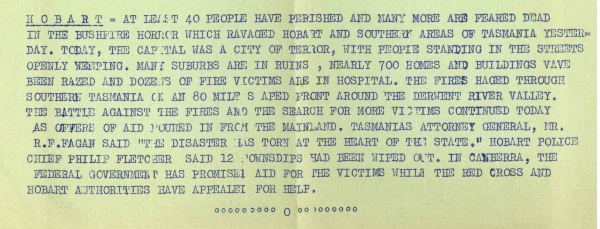

It was just as well we heard about my family’s loss before we reached the dining room, because when we got there we picked up a copy of a one foolscap-page gestetnered news-sheet, the AUSTRALIAN SHIPRESS news for Thursday, 9 February 1967. The seventh item on it (news from Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra was clearly considered more important) was datelined HOBART and said:

A photograph of a portion of the M.S. Aurelia’s AUSTRALIAN SHIPRESS news-sheet

that

was issued on Thursday, 9 February 1967.

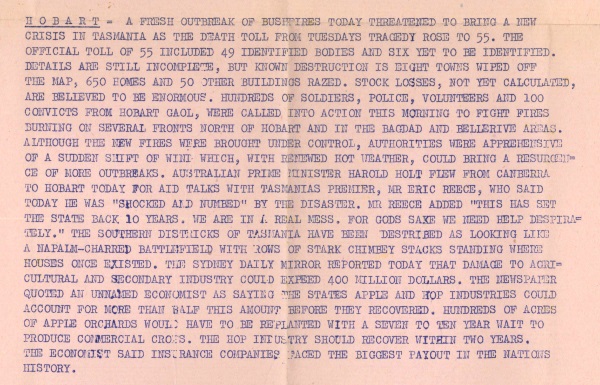

Two days later, the next edition of the AUSTRALIAN SHIPRESS news not only promoted news of the Tasmanian bushfires to third in importance, but also gave more details about the fires, including the fact that the death toll had risen to 55. Here’s a photograph of the relevant paragraph:

A photograph of a portion of the M.S. Aurelia’s AUSTRALIAN SHIPRESS news-sheet

that

was issued on Saturday, 11 February 1967.

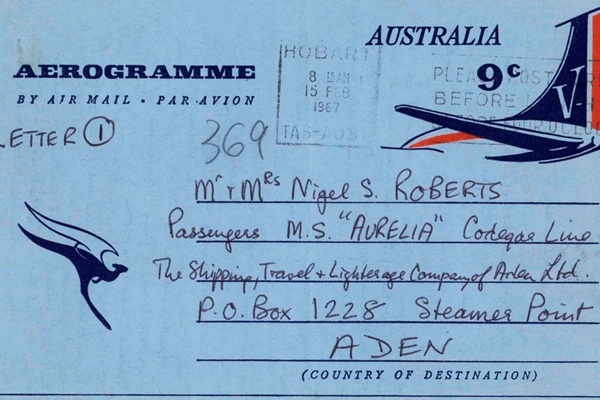

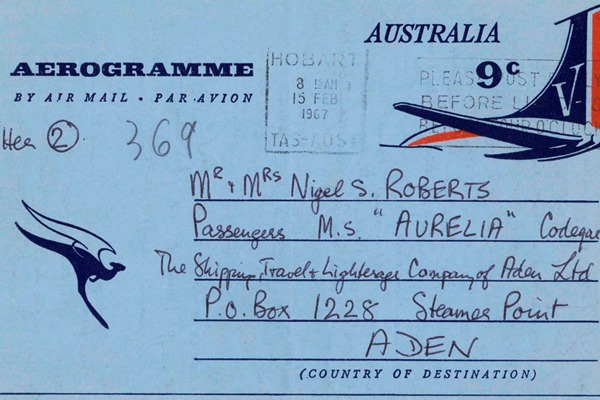

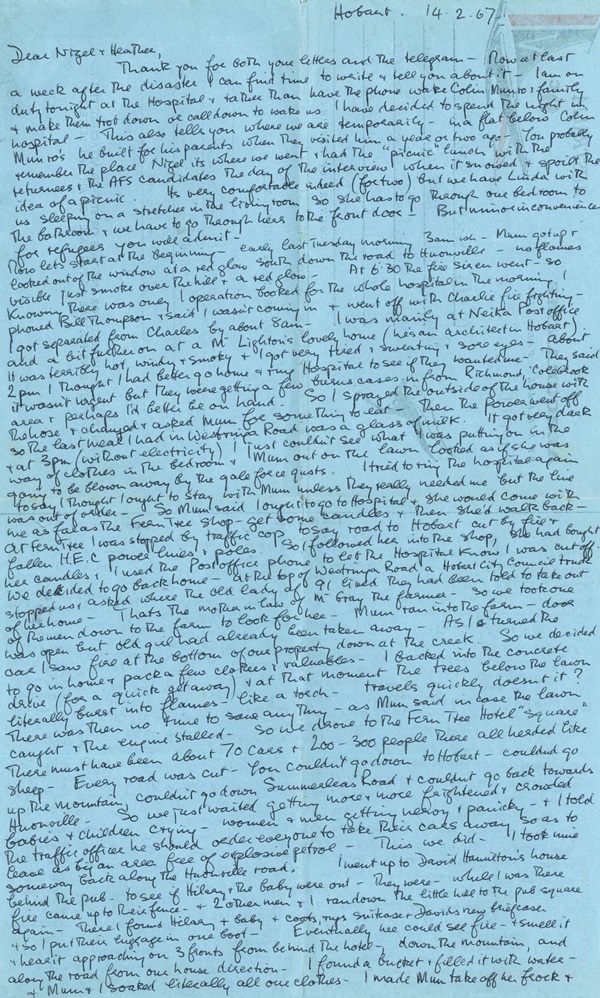

After stopping in Perth (where we telegrammed my family care of the Royal Hobart Hospital: we couldn’t ring them because we neither knew where they were staying nor did we have a phone number for them), the M.S. Aurelia headed northwest across the Indian Ocean (on its way, first, towards the Suez Canal, and then to Genoa). Almost two weeks later we docked briefly in Aden. My father had sent two aerogrammes to us in Aden, detailing – in more than 2,200 words – what had happened on Black Tuesday and its immediately aftermath.

Photographs of the two aerogrammes that my father, Bobby Roberts, wrote on Tuesday,

14 February 1967, and sent to Heather and me in Aden.

The letters were delivered to Heather’s and my cabin shortly after the Aurelia started sailing up the Red Sea. We read them over and over again, and nearly 50 years later, the letters are amongst my treasured possessions. They make very dramatic reading: I still marvel at the fact that my mother and father weren’t among the victims of the 7 February 1967 bushfires: there were several times when they could so easily have been.

The first of the four pages of the two-part letter that Bobby Roberts wrote

on 14 February 1967

describing his and his family’s experiences during Tasmania’s Black Tuesday bushfires.

********** |