|

NIGEL S. ROBERTS Travels with a Brother in the Cape |

|

One of Robert Louis Stevenson’s earliest books, which was initially published in 1879, is Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. Stevenson’s account of his 12-day trip in France is regarded as “a pioneering classic of outdoor literature”,[1] and many people now retrace his steps from Le Monastier, 15 miles from Le Puy in the Haute-Loire region, to St Jean du Gard by following what has become known as the Stevenson Trail. It is to R.L.S. that I owe the inspiration for the title of this essay.

As a teenager I went on three hitchhiking trips in southern Africa. My first trip began on 11 December 1959, and I hitchhiked from Johannesburg to Moshi (in what was then called Tanganyika) and back. By the time I returned home on 3 January 1960, I’d covered 5,796 miles / 9,328 kilometres – half of which was with a hitching companion, Garth Hoets, and half (the return trip) was on my own. In terms of both time (24 days) and distance, it was the longest hitchhiking trip I went on in Africa. Six months later, a friend – Richard Darley – and I spent 15 days hitchhiking 2,469 miles / 3,973 kilometres mainly round Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). My third and last hitchhiking trip in Africa was in January 1961, and it was unique in a number of ways. It was narrowly – namely, by one day and just over a hundred miles / 160 kilometres – my shortest African hitchhiking trip. More significantly, though, it was the only hitchhiking expedition that I ever went on with any of my brothers.

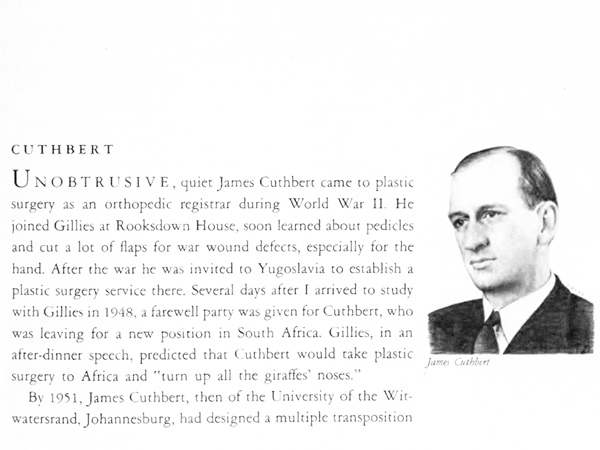

After spending the second half of December 1960 at home during the summer holidays, the prospect of four more weeks at home seemed unutterably stultifying. I yearned for action and excitement. After my adventures on Mt Kilimanjaro the previous summer, and my hitchhiking trip to Rhodesia the previous winter, I had seriously itchy feet. I was sixteen-and-three-quarters years old. My younger brother, Stuart, was fourteen-and-a-half. I asked him if he’d like to come on a trip with me. He was keen, but we didn’t think our parents would let Stuart go hitchhiking with me. To our complete surprise, they did. As I have commented elsewhere, what wonderfully “tolerant, liberal and trusting parents” we had![2] Even in retrospect, though, I find it hard to conceive that Mum and Dad would have let us – a 16- and a 14-year-old – go hitchhiking together. They went further than that. They helped us work out where we should go. Dad had a medical friend in Kimberley, which was – if luck was on your side – within an easy day’s reach of Johannesburg. We could go there first, a city we’d never been to, and see the famous Big Hole – a former diamond mine. After that, Mum and Dad suggested Stuart and I could head on down through the Cape Province and visit friends in Hermanus. We had holidayed there three times when Stuart and I were in primary school, and Mum and Dad knew that the friends who had facilitated our accommodation in Hermanus in the early- and mid-1950s were currently holidaying there. As a result, Mum and Dad wrote to our friends, Jim and Joan Cuthbert, to let them know that Stuart and I would be hitchhiking to Hermanus and to ask if we could possibly spend a few days with them. After Hermanus, Stuart and I reasoned we could try to return to Johannesburg via the famed Garden Route, which we’d not been on before. The Garden Route extends for roughly 200 miles along the south-east coast of South Africa, and is renowned for its lush vegetation and coastal scenery.

With minds made up, plans hatched, and parental approval (well, it was actually encouragement), we were ready to begin our fraternal adventure. On the day of our departure ... We reached Uncle Charlie’s shortly before 7:00 am. Mum said goodbye to us (I do wonder if the thought crossed her mind that she might not see two of her four sons again), and Stuart and I started hitchhiking.

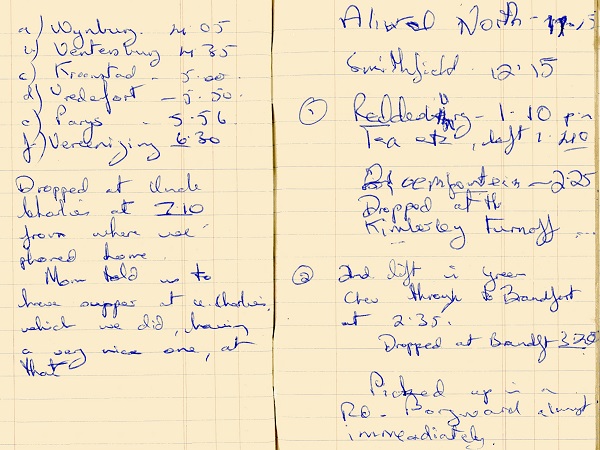

We waited only two minutes before we got our first ride in a green Chevrolet Biscayne. An hour later we’d covered almost 70 miles and were in Potchefstroom, where we stopped for coffee, after which our first ride of the day continued for another 23 miles as far as Stilfontein, where we were dropped at 8:40 am. Stuart and I then walked for twenty minutes (the name of the game was, after all, hitchhiking) until we found a good spot to stop and wait. My two previous hitchhiking trips had taught me that one of the key elements for successful hitchhiking was standing in the right location: not surprisingly, you clearly faced the cars coming towards you, but there had to be enough space in front of you to enable you to be seen easily by car drivers, and there also had to be enough space behind you for a fast car to pull over and stop safely. My experience was quickly rewarded: five minutes later two travelling salesmen in a grey Jaguar stopped, picked us up, and took us to Klerksdorp. It was a ride of only ten miles – but they were a stylish ten miles. Compact cars

Lift number four was in far more compact car with an even more interesting history – a Volkswagen beetle. The 'people’s car' was first produced in 1938 with strong support from Hitler and the Third Reich. Few were produced before World War II, but Volkswagen flourished after the war and became what has been called an “icon of post-war West Germany.”[5] They had a mixed reputation in Africa. An advertising jingle promoting them in South Africa had a catchy tune and consisted of the following lines:

However, possibly apocryphal stories abounded of VWs being caught in the slipstream of large lorries speeding in the opposite direction and the small beetles flipping over as a result, and that led us as schoolboys to change the words of the ditty and instead sing, “Volkswagen, Volkswagen, Turning upside down.” In addition, a schoolyard joke asked “Why do Volkswagens have two exhaust pipes?” Answer: So you can use it as a wheelbarrow when it turns over. On the other hand, VW beetles were renowned for handling slippery, muddy conditions on the unpaved roads that were prevalent in many parts of Africa. I had personally experienced their versatility in the longest single ride I have ever had as a hitchhiker. Twelve months earlier, I’d got a 1,577-mile long ride in a Volkswagen that over the course of two days had taken me from the Tanganyika-Northern Rhodesia border to Potgietersrust in South Africa. As I have written in my account of that trip, during the first day of the ride, “the road was thick with mud, but the small Volkswagen successfully slithered its way south. Dirk and Sarel explained proudly how good VW beetles were at handling the sticky, slippery conditions, and pointed out to me how many VWs were able to get through the mud and how many other vehicles weren't.”[6] As a result, I was delighted to be back in another VW beetle. Sadly, though, the Volkswagen took us only from Wolmaransstad to Kingswood – a distance of about 25 miles. That wasn’t a problem, though, because at 10:45 am, after a ten-minute wait, Stuart and I got our fifth and longest lift of the day – for about 110 miles – in a red Renault Dauphine. It took us to Windsorton, which we reached at 12:20 pm. In the early 1960s, cars drove fairly fast in South Africa. The roads were good and the traffic was light. As a result, the small red Renault that took us from Kingswood to Windsorton was driven at about 70 miles per hour (i.e., 110 kilometres per hour) – higher than the current legal speed limit in New Zealand – and, as we were to discover the next day, that wasn’t especially fast. We were already in the Cape Province. Our sixth and final lift for the day (in a Borgward Isabella) picked us up only five minutes after we were dropped off in Windsorton by the red Renault, and we were in Kimberley by 1:00 pm. Stuart and I found a café, where we bought ourselves some lunch, and then contacted Dad’s friend, Dr Shein.Breaking the butchers' mould During World War II, Abe Shein had practiced medicine in London. While there, he passed his Diploma in Anaesthetics exams in November 1941, and Abe Shein worked as an anaesthetist at Guys Hospital during the Blitz, when “casualties were operated on in an improvised four-table operating theatre in the cellar. The operations went on day and night, even though the hospital itself was heavily damaged. On five occasions the daily total of admissions was more than 100. This intense activity was repeated later in the war during the V1 and V2 attacks of 1944 and 1945.”[7] I assume that this was how Dad and Abe Shein knew each other, because Dad, too, had been an anaesthetist in London during the Second World War, when he worked at the Middlesex Hospital. Dad has described in detail his memories of working as a doctor in wartime London, and they have been published on the Royal College of Anaesthesia’s website. Here is a brief extract from them:

Dr Shein collected us in an Opel at 2:00 pm from the café where we’d had lunch, and dropped us at the Big Hole, which was what Stuart and I had primarily come to see in Kimberley. Diamonds were first found in what is now Kimberley in 1871. In the ensuring frenzy (indeed, Kimberley was initially called New Rush) up to 50,000 miners using picks and shovels dug a massive hole that eventually covered 42 acres and was over 460 metres deep. Now partially filled with debris and water, the hole is only visible to a depth of about 175 metres. Nevertheless, it was – and still is – an impressive sight.

Afterwards, Dr Shein took Stuart and me to see the TB Hospital (where he did some of his work) and the Duggan-Cronin Bantu Gallery, which to this day still houses some of the photographs taken by and artefacts collected by the photographer, Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin. Many of his photographs can also be found in the Wellcome Collection in London. My trip notes record the fact that I found the Gallery “very interesting.”[9]

At about 5:00 pm, Dr Shein took Stuart and me to his house for a “scrumptious” afternoon tea, and just before 7:00 pm we drove to Riverton, which was also known colloquially as Kimberley-on-the-Vaal, for a swim in the impressively large Vaal river, followed by a braaivleis – which is the Afrikaans term for a barbecue. We got back to Dr Shein’s house “quite late”, so instead of erecting a tent on his lawn (which had been our initial plan), Dr Shein suggested that Stuart and I simply sleep on a double lilo on his stoep, an Afrikaans word (and also a Dutch word) for a veranda or porch (and interestingly it’s also a word that’s used – though spelt “stoop” – in New York, a city that was once known as New Amsterdam), which is what we did. We had done a lot in one day and were both very tired. Rhodes and rides

We were then taken to the Dutoitspan Mine, part of the De Beers mining group, where we saw the mine’s above-ground operations, including all the diamonds – still uncut – that had been mined two days earlier. The mine tour included a visit to “the Native hostels” in which the mine’s African staff were housed. The tour guide proudly proclaimed that, unlike many mines in South Africa, De Beers did not give its employees free food but, instead, paid them “higher wages [so] they can buy food cheaply on the mines.”

Dr Shein’s driver met us at the mine shortly before 12 noon and took us back to the house. After Stuart and I had had lunch and repacked our rucksacks, Dr Shien’s driver then drove us out to the main Kimberley-to-Cape Town road, where he left us at 12:45 pm. The afternoon didn’t get off to a promising start: Stuart and I sat and waited by the roadside for half-an-hour before we got our first lift – in a crowded Volkswagen Kombi – and it was only to Modderrivier, a little more than 20 miles south of Kimberley. However, our luck changed quickly (and quickly – as we shall see – was indeed the operative word). After a short wait, we got our second – and, as it transpired, final – ride of the day. A man who was possibly a travelling salesman driving a large green-and-grey Chevrolet stopped to pick us up. He already had one hitchhiker in the car, a Stellenbosch University student, and sometime after picking up Stuart and me, he picked up a fourth hitchhiker, a young Afrikaans-speaking man from Booysens, a suburb in Pretoria. I made a note of the car’s licence plate in my diary. It was CER 170. In the 1950s and early 1960s, South African licence plates were a handy guide to where cars came from. Cars from the Transvaal had licence plates beginning with T; cars from Natal began with N; cars from the Orange Free State with O; and cars from the Cape Province with C. The letters that followed then identified the town or city the car came from. TJ, for instance, showed that the car was from Johannesburg. Likewise, cars with licence plates beginning ND were from Durban, and cars with OB plates were from Bloemfontein. Cars from the Cape Province had a slightly different system. Instead of using the second and third letters to align, where possible, with a city’s name (such as NP for Natal Pietermaritzburg), Cape Province plates favoured size: CA was the prefix for Cape Town, the province’s capital and its largest city, and CB was the prefix for Port Elizabeth, the second largest city in the Cape. Incidentally, the first car that Dad bought in South Africa, a 1948 Chev, had the licence plate TJ72236. I can still remember the number because Dad pointed out to me that 72 divided by 2 is 36. Ever since then I’ve tried to convert licence plate numbers into mathematical formulae. I simply cannot help doing it. If I see, for instance, KE3715 (which was the number plate of a Ford Laser that Heather and I once owned), I immediately find myself thinking 3=(7+1)-5. The two main self-prescribed rules of the game are, first, that you cannot change the order of the numbers; and, second, that you can use any mathematical symbol. In this regard I should point out that knowing that you can change 3, for example, into 6 by using a factorial sign (3!=3x2x1=6) renders many licence plates more amenable to formula-making! Hitting a hundred

It was, though, a stop-start ride. The Chevrolet’s driver covered the 135.5 miles from Modderrivier to Britstown in an hour and 25 minutes (at an average speed of 95 miles / 153 kilometres an hour). We then spent 35 minutes in Britstown having a drink and rest before he raced off again (at an average of just under 90 miles an hour) to Victoria West, where he stopped for 50 minutes because, as I noted in my diary, “our ‘cowboy driver’ had some business.” Later on, after leaving Beaufort West at 7:00 pm, it began to get dark, and the Chevrolet’s average speed dropped to a little over 60 miles an hour. After we’d driven up and over the Hex River Pass, I fell asleep but woke up when we reached Paarl at 11:00 pm. Thirty-five minutes later, we arrived at our driver’s destination, Belleville, and he dropped all four of us outside the local police station. Stuart and I had been in his car for nine-and-a-half hours, and we’d travelled a total of 582 miles with him. The Stellenbosch University student was fairly close to his destination, so even though it was getting on for midnight, he decided he’d carry on hitchhiking. However, the remaining three of us – the “jaapie” (i.e., the young Afrikaaner) from Booysens, Stuart, and I – went into the Belleville police station and asked if we could stay there for the night. As I have explained in my account of my first African hitchhiking trip, “in the absence of youth hostels and what we now call backpackers' hotels in Southern and Central Africa in the late 1950s and early 1960s, there was an understanding (if not an explicit rule) that the police would put hitchhikers up for the night.”[10] On previous trips I’d stayed in police stations in South Africa, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), and Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Not once had I ever been turned away from a police station, and the Belleville police didn’t prove to be an exception to the rule. The three of us were “put up in an empty room [where] we had a fairly comfortable night.” Stuart and I were carrying a sleeping bag apiece in our rucksacks, but not sleeping mats, but we were young and tough in those days, and it clearly didn’t affect us too greatly."Hermanus holidays were wonderful" Our family loved Hermanus. An extract from my father’s Memoirs explains why:

As a result, Stuart and I were thrilled to be back in Hermanus for the first time in six years or so.

We walked from the Marine Hotel to where the Cuthberts were staying a little more than half-a-kilometre away in a house called “Seriola” at 76 Mitchell Street. When I wrote the initial version of this essay in May 2019, I consulted Google maps to determine the precise location of 76 Mitchell Street, and – as a result – I expressed

It was, I concluded, “a mystery I suspect I’ll never be able to solve.” I was definitely wrong in that regard, because I went back to South Africa in September 2019 in order to visit Stuart’s and my youngest brother, Charlie. While I was in South Africa, I went on a nostalgic trip to Hermanus partly to see whether I could work out where we’d stayed when we holidayed there in the early 1950s. Aided by a black-and-white photograph of Stuart standing arms akimbo alongside Charlie in the front garden of the cottage we’d stayed in, I searched for a property with the same backdrop.

By dint of dogged detective work and sheer luck, I found it. Looking northwest from 6 Nichol Street, the view of the hills was partly obscured by a house with a green tiled roof on the other side of the road.

However, enough of the ridgeline of the hills behind Hermanus was visible for me to work out that the hilltop bumps and undulations in the two photographs – one taken in early 1953; the other taken more than 66 years later – were perfectly aligned.

Stuart’s and my arrival at 76 Mitchell Street was somewhat embarrassing. For a start, the letter Dad had sent the Cuthberts telling them that Stuart and I were hitchhiking to the Cape hadn’t arrived. That was, as I noted in my diary, “as expected.” Not only would mail deliveries have been slower than usual during the Christmas / New Year holiday period, but the South African Post Office also had a poor reputation. A well-known (though admittedly probably apocryphal) story in South Africa at the time was that post office workers had staged a go-slow strike, but they had called it off after a fortnight because no one had noticed the difference. To make matters worse, Stuart and I had been at boarding school for a couple of years, and although our parents had seen and socialised with Jim and Joan Cuthbert during that time, we hadn’t and when we rolled up at her holiday house door at 9:15 in the morning, Joan didn’t recognise us. Thankfully, it wasn’t long before “everything was sorted out” and Joan told us we could stay with them. As Stuart and I hadn’t had much to eat since leaving Kimberley, the next thing Joan did was give us a large and very much appreciated breakfast. The Cuthbert connection

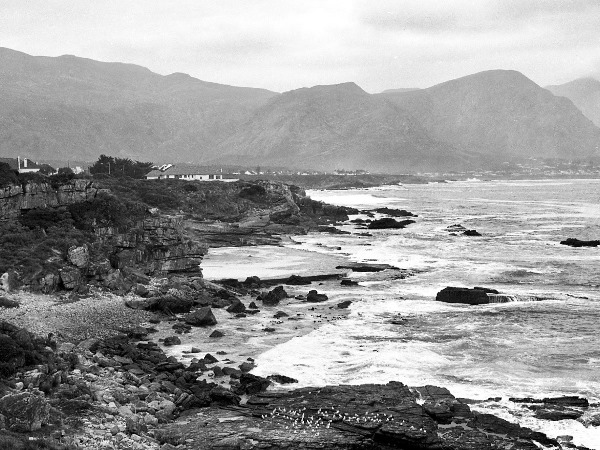

Stuart and I spent four days in Hermanus with Jim and Joan Cuthbert, their sons Andrew and Drummond, and a family friend named John Sheffield. They were archetypically halcyon summer days. We went swimming at Grotto beach. We walked up Hoy’s Koppie (a hill near the centre of the town which has a grand view out over the town, the harbour, and the bay). We fished (unsuccessfully) at New Harbour. We went out on the lagoon in the Cuthberts’ dinghy (like their house, it too was called the 'Seriola', which was a highly appropriate name for a little fishing boat, because it’s the Latin term for a yellow tail fish): while we were fishing from the 'Seriola', we all caught at least one fish and between five of us our total haul was eight steenbras and four stumpnose.

We tried spear-fishing in the marine pool – but like our New Harbour attempts to 'spin' for yellow tail – we came away empty-handed. And one evening, we all (bar John Sheffield, who was ill) went to the local cinema to see Sink the Bismarck, a classic British war film starring Kenneth More (incidentally, I wonder whether any actor appeared in Second World War movies more than More – he was, surely, to war films what John Wayne was to cowboy movies).

While we were in Hermanus, I also spent quite a lot of time in a range of locations trying to photograph waves breaking on the town's rocky shores. Anticipating when the raw power of the sea hits the land to maximum effect isn't always easy, but I enjoyed the challenge then – and, what is more, still do so six decades later.

After four delightful days, however, it was time to leave the Cuthberts in peace. On Tuesday, 10 January, Stuart and I got up at 6:45 am, packed, had breakfast, and said our farewells before Jim drove us out of town and dropped us at a nearby village called Onrus. The Cuthbert family had been extremely hospitable to us, so I was very sorry to learn roughly three years later that “after a lengthy illness with severe residual pain” (to quote from a chapter in a book about plastic surgery), Jim committed suicide.[14] I don’t know what Andrew, who was a year younger than Stuart, went on to do in life, but Andrew’s younger brother, Drummond, eventually moved to Britain and became a well-known picture-framer and gilder. Nearly 30 years after his father’s death, Drummond took part in a BBC radio documentary series called Going Back. According to the programme notes for the broadcast, Drummond travelled “back to the northern suburbs of his South African youth and to the memory of his father, a distinguished surgeon who took his own life when Drummond was 13 years old.”[15] It’s a programme I would have loved to have heard. On the road again Stuart and I climbed out of the ute, shouldered our ruck-sacks, walked along the road for a while, and then sat on the roadside and waited … and waited. To pass the time, I wrote a small poem which I entitled The Glacier:

There was another verse, but it was worse.

Two hours later, we walked back towards the town in search of a café. Refreshed by a soft-drink and an ice-cream (what a healthy diet), we returned to “a suitable spot outside the town” and resumed hitching. At 3:45 pm – after a wait totalling three-and-a-quarter hours – a truck (not a pick-up, but a real truck, which was often referred to as a lorry in South Africa) stopped to pick up not only Stuart and me, but also two other hitchhikers. We were in luck: the driver said he could take us all the way to Plettenberg Bay. Compared with most of our previous rides, the lorry was fairly slow. Nevertheless, we passed through Swellendam at 4:35 pm, Heidelberg at 5:25 pm, Albertina at 6:20 pm, and entered Mossel Bay at 7:00 pm. We had covered more than 175 miles in three-and-a-quarter hours, so were averaging almost 55 miles per hour. We stopped in Mossel Bay for ten minutes to fill up with petrol (or, possibly, I presume, diesel) and then carried on, with Stuart and me now sitting in the driver’s cab. Twenty minutes later, just after we crossed the Great Brak river, the lorry had a puncture. The driver had previously had another puncture and had already used his spare tyre. He wasn’t daunted, however. As the back axle had a total of four wheels – two on the left and two on the right, our driver simply opted to continue driving with just one tyre – and not two – on the right-hand back wheels, and he now had two punctured tyres in the back of the lorry. As I noted in my diary, “it was a rather frightening journey” through to Plettenberg Bay. The sun had already set when we passed through George at 8:00 pm and it was dark by the time we drove through Knysna at 9:15, so we didn’t see either the famed Knysna Heads or some of the Garden Route’s other stunning scenery. The lorry driver dropped us off in Plettenberg Bay at 9:50 pm. Although it had been a stop-start day, Stuart and I had still covered more than 300 miles in just three lifts, and we had safely reached our intended destination. We went into the Plettenberg Bay police station, and without any hesitation were told we could sleep on the station’s stoep. We got out our sleeping bags and settled down for a reasonable (though not especially comfortable) night’s sleep. Plettenberg Bay When Stuart and I woke at 6:15 am on Wednesday, 11 January, we saw a man sorting out newspapers prior to his morning paper-round. I had a brain-wave and asked the newspaper vendor if he knew where Dr Black’s house was. He did indeed. It was easy to find: its address was simply The Pink House, Plettenberg Bay. Armed with that knowledge, Stuart and I found a cafe where we “had a snack” and each bought a novel (mine reflected my interest in mountain climbing: First on the Rope).

We returned to the police station, picked up our packs, and made our way to the Blacks' Pink House. Brian’s mother and his sister, Claire, were at home when we knocked on the door and explained who we were to Mrs Black, whom neither Stuart nor I had met before. The sight of two somewhat scruffy boys didn’t deter Mrs Black. She told us that Dr Black, Brian, and his older brother Michael were out fishing at the Point and that they planned to spend the night there. As a result, she said we simply must stay – and not only spend that night but the next night as well – with them, otherwise we wouldn’t be able to see and spend time with Brian. Of course, Stuart and I were happy to do so: after all, that’s what we had hoped would happen.

Around noon, Michael came back to the house to collect Claire and take her to the Point as well, but before he did so, Claire, Michael, Stuart, and I went to the Beacon Island beach for a swim. “The waves,” I noted in disgust, “are pathetically small.” The four of us then walked out along the Robberg peninsula to the Point. Michael and Claire stayed there, as planned, together with Brian and Dr Black, for the night, while Stuart and I returned to the Pink House and had dinner with Mrs Black. Forging a friendship

Dr Black, Michael, Brian, and Claire came back to the Pink House early on Thursday afternoon, 12 January, and Dr and Mrs Black suggested that Stuart and I stay longer in Plettenberg Bay – until after the weekend. As a result, Brian, Claire, Stuart and I spent four very pleasant days in each other’s company. We swam; we walked; we played cards (a game that was called pontoon in South Africa: it’s often known elsewhere as 21, a variant of blackjack, and the name 'pontoon' is a bastardisation of the French for 21 – namely, vingt et un); and we fished, albeit unsuccessfully. We also went to Knysna to see the famous Heads, which Stuart and I hadn’t seen in the dark on our way to Plettenberg Bay, but which I huffily judged to be “over-rated”.

On Saturday evening, 14 January, we went to a dance – to a “hop” as we teens called it – at the Beacon Island Hotel. Two other boys from our school, Gordon and Grahame Martin, were there, and we enjoyed their company, but as pupils at an all-boys’ boarding school, Brian’s, Stuart’s, and my social skills were somewhat under-developed and, as I noted in my diary, we “did not dance".

The whole Black family were remarkably generous and hospitable. Stuart and I really enjoyed our time with all of them, but all good things come to an end, and on Monday, 16 January, it was time for Stuart and me to hit the road again. After we’d packed and had a large breakfast, Dr Black dropped us on the road out of town at 8:25 am. Fifteen minutes later, we got our first ride in a red Vauxhall Velox, which took us all the way through to Port Elizabeth, but at 12:30 pm we were dropped off at the wrong intersection. On the outskirts of the second-largest city in the Cape Province, Stuart and I rightly wondered how we were going to reach the right road, because as events transpired it took us two more hours and three short lifts – in a grey Peugot station wagon, in a grey Jaguar, and in a crowded Chevrolet pick-up truck – to get to the right road (that is, to the Grahamstown road). Once there, though, our luck soon changed for the better. At 2:30 pm, G. W. Ellison from Douglas in the northern Cape, near Kimberley, picked us up in his Land Rover. He was heading home, but first detouring to East London to drop off his daughter. As a result, he initially drove us via Grahamstown and King Williams Town to East London, which we reached at 6:05 pm. An hour later, after he’d said goodbye to his daughter, Mr Ellison then turned round and headed west, back to King Williams Town, which we passed through at 8:10 pm. Fifty minutes later, we pulled into Stutterheim. After we had a meal in a café, Mr Ellison checked into a hotel for the night, while Stuart and I slept in the back of his Land River in the hotel’s carpark. All in all, our day’s hitchhiking had seen us cover more than 400 miles. Lucky to be alive

After waiting for only ten minutes, Stuart and I got our second lift of the day – once again, it was in a Chevrolet, but it was only as far as Brandfort, which is 36 miles north of Bloemfontein. At 3:25 pm, five minutes after we were dropped off in Brandfort, we scored our third and final lift for the day. A driver in a red Borgward picked us up. He didn’t drive excessively fast, He averaged only a little more than 63 miles per hour: we passed through Wynburg at 4:05 pm, Kroonstad at 5:00 pm, Vredefort at 5:50 pm, and Vereeniging at 6:30 pm. However, he was a careless and occasionally utterly reckless driver. At one stage, orange barrels blocked off one of the road’s lanes. Our Borgward driver ignored them, skirted round the barrels and proceeded to drive through the road works in the forbidden lane. I was petrified. It was the scariest ride of my life, and as we approached Johannesburg, I asked him if he could drop us off at Uncle Charlie’s. Although he was heading north through the city, I didn’t want to spend one more minute in his car. Thankfully, our driver didn’t turn nasty and he stopped to let Stuart and me out of the car at Uncle Charlie’s at 7:10 pm.

We were back to where we’d started hitchhiking almost fourteen days earlier. We had only hitchhiked on six of the days (we’d spent the rest of our time, of course, in Hermanus and Plettenberg Bay), but during those six days we’d had 22 lifts and had covered a grand total of 2,331 miles. We used the public phone box at Uncle Charlie’s to ring home. Mum answered and said that as she and Dad were about to have their dinner, Stuart and I should have our dinner at the roadhouse, and that she’d come out later to collect us, which we duly did and which she duly did. When Mum arrived at Uncle Charlie’s some time after 8 o’clock, we told her how pleased we were to see her: in light of the last lift we’d had, both Stuart and I felt that, in some respects, she was lucky to see us alive. My travels with a brother in the Cape were the last time I hitchhiked in Africa. I only ever went on one more major hitchhiking trip – six-and-a-half years after my January 1961 trip with Stuart, my wife Heather and I hitchhiked from Farnham in England to Worms, Germany, and back. After looking back at my January 1961 diary and the notes that I wrote at the time, I want to end this essay by quoting some of Robert Louis Stevenson’s words in Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes:

Thank you, Stuart – brother; honest friend; and certainly not a donkey. ***************

[2] Nigel S. Roberts, “Climbing America’s ‘Purple Mountain Majesties … From Sea to Shining Sea’”, New Zealand Alpine Journal, 2018, p. 84. [3] Robert Louis Stevenson, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (London: Chatto & Windus, 1907, p. 10. [4] See https://auto.howstuffworks.com/1956-1957-rambler.htm (accessed 19 May 2019). [5] See http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ (accessed 19 May 2019). [7] See “Kilpatrick, Francis Rankin (1908-2005)”, Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows (London: Royal College of Surgeons, n.d. – "rcs: E000331" (accessed 19 May 2019). [8] F. W. (Bobby) Roberts, Memoirs (1911 to 1973), p. 112. See https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/RobertsFW-Memoirs_Part2.pdf (accessed 19 May 2019). [11] F. W. (Bobby) Roberts, Memoirs (1911 to 1973), p. 194. See https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/RobertsFW-Memoirs_Part3.pdf (accessed 19 May 2019). [12] See B. J. S. Grogono, “Changing the hideous face of war”, British Medical Journal, vol. 303m 21-28 December 1991, pp. 1586-1588. [13] D. Ralph Millard, Jr., Cleft Craft: The Evolution of its Surgery (Boston: Little, Brown, 1980), volume III, p. 449. [14] D. Ralph Millard, Jr., Cleft Craft: The Evolution of its Surgery (Boston: Little, Brown, 1980), volume III, p. 450. [15] See https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/schedules/radio4/fm/1992-06-18 (accessed 19 May 2019). [16] Robert Louis Stevenson, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes (London: Chatto & Windus, 1907), p. vii. Picture credits 004a: This map of South Africa was made available on the https://www.ezilon.com/maps/africa/south-africa-road-maps.html website. 004b: This advertisement for a ’59 Rambler appeared in The Saturday Evening Post on 28 February 1959. 004c: “The Volkswagen Theory of Evolution” image was reproduced by courtesy of Volkswagen AG and made available on the https://www.vintag.es/2019/01/the-volkswagen-theory-of-evolution.html website. 006: The photograph of the Duggan-Cronin Gallery was taken by Andrew Hall, CC BY-SA 3.0 (see https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/ index.php?curid=21355847). 007: The photograph of Ben Mdilizza, a Shangaan warrior sitting on a rock holding a skin shield, was taken by Alfred Martin Duggan-Cronin and is in the McGregor Museum, Kimberley. 009: The photograph of the Chevrolet was made available on the https://www.cargurus.com website. 011: This is an extract from D. Ralph Millard, Jr., Cleft Craft: The Evolution of its Surgery (Boston: Little, Brown, 1980), volume III, p. 449. 014: The Sink the Bismarck poster was made available on the https://www.picturepalacemovieposters.com website. 016: The photograph of the Robberg peninsula and the Point was made available on the https://www.cedarberg-travel.com/africa-faqs/knysna-vs-plettenberg-bay website. 021: This map of South Africa was made available on the https://www.ezilon.com/maps/africa/south-africa-road-maps.html website. ********** |

||