|

NIGEL S. ROBERTS Climbing Aconcagua, 1994-95 |

|

"The Seven Summits" is a phrase that entered mountaineering literature — and captured the public's imagination — when Dick Bass and Frank Wells published their 1986 account of their five-year quest to climb the highest mountains on each of the earth's seven continents. Cerro Aconcagua, the tallest mountain in South America, is the second highest of the Seven Summits — only Mt Everest is higher (which means that Aconcagua is, of course, the highest mountain in the world outside Asia).[1]

Aconcagua: Stone Sentinel and Malevolent Mountain In the Aymara language, Aconcagua means "sentinel of stone." As a result, at least two books about the mountain have almost identical titles (namely, Alejandro Randis and Maria Marta Lavoisier's Aconcagua: The Sentinel of Stone and Thomas Taplin's Aconcagua: The Stone Sentinel). There is also widespread agreement on the fact that Aconcagua is a rather mean mountain. In November 1994, I read two articles about climbing Aconcagua. One was entitled "Malevolent Mountain"; both contained dramatic accounts of deaths on the mountain. On the 1989 expedition to Aconcagua that was the basis of Taplin's book, only four out of sixteen people reached the summit; and in an article simply entitled "Climbing Aconcagua", William Broyles (a former editor-in-chief of Newsweek) wrote, "Of the sixteen of us who had begun the climb, six made it to the summit." It is noteworthy, too, that Aconcagua was the only peak which a group of Norwegian mountaineers didn't conquer in 1992 when they tried to climb the highest mountains on five continents in just five weeks (an attempt described in Fem Fjell, Fem Kontinenter, Fem Uker, Stein Aasheim and Ivar Tollefsen's brilliantly illustrated account of the lavishly funded expedition). Overall, it is said that there is a success rate of 30 per cent on the mountain: seven out of every ten people who set out to climb Aconcagua don't reach the summit.

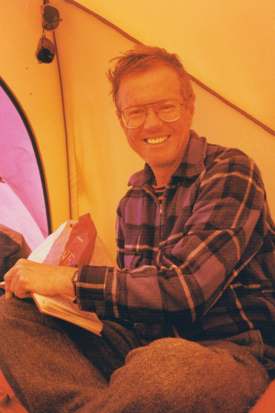

Despite these statistics, I'd decided in early 1993 to try to climb Aconcagua. After a successful attempt to climb Mt Kilimanjaro in December 1985 and an unsuccessful attempt in October 1991 to scale Lobuje East, a 6,119 metre / 20,075 foot peak in the Himalayas, I had formulated a personal "Three-and-a-Half Summits" goal — i.e., I would try to climb at least three of the six tallest Seven Summits, as well as climbing Mt Kosciusko (which, although it's the highest mountain in Australia, is only 2,230 metres / 7,316 feet high, and thus rates as a "Half Summit" in my book). I knew I was going to be based in Scandinavia on sabbatical leave during the second half of 1994, and during the first half of 1993 thus set about investigating the possibilities, first, of climbing Elbrus while I was in Europe and, second, of climbing Aconcagua on my way back to New Zealand. In March 1994 I signed up with an American adventure travel company, REI, to go to Russia in August 1994 on one of its Mt Elbrus expeditions. Although I had boiled my choice for Aconcagua down to two companies — one American (the American Alpine Institute, based in the state of Washington) and one British (Himalayan Kingdoms Ltd, based in Bristol), I also decided not to make a decision about climbing Aconcagua until I'd seen how I'd fared on Elbrus. Less than half an hour after we began our descent from the summit of Mt Elbrus, Greg Matte — one of six Americans who climbed the mountain with me — said, "I've a question for you, Nigel, but you needn't give me a definite answer now if you don't want to." I knew immediately what the question would be: "Do you still want to climb Aconcagua?" I was exhausted after our ascent of Elbrus, and told Greg that at that stage my answer was Yes and No. However, time quickly dulls memories of tough times on mountains and soon only the highlights shine through, so much so that less than three-and-a-half weeks later I began the process of clarifying which company I'd chose for climbing Aconcagua, and on 13 September 1994 — a month to the day after reaching the summit of Mt Elbrus — I signed up with Himalayan Kingdoms to go on their 16 December 1994 to 9 January 1995 Aconcagua expedition. A few days later I was in Stockholm and sent Greg a postcard (of an ancient Swedish urinal) to tell him of my decision. The envious lad replied with a prompt postcard saying, "Nigel, ... you bastard"! Raining and Training

On 12 December, the day I left Britain to fly to Argentina, I ran up London's Primrose Hill and around Regent's Park and achieved three targets: first and foremost, I felt fit; second, I had successfully completed more than forty training runs since the end of September; and, third, I'd run on at least 150 occasions during the year. My main concern, however, was that my training had been at very low altitudes — not even a gruelling cross-country race that began and ended atop one of the highest points in Denmark, the Himmelbjergløbet — i.e., the Heavenly Mountain race, was much help, for the summit of Himmelbjerg is only 147 metres / 482 feet above sea-level! It's a very long way from the top of Denmark's Heavenly Mountain to the summit of Argentina's Stone Sentinel ... 6,815 metres / 22,359 feet to be precise. Apart from a change of airports and planes in Buenos Aires, I flew directly from London to Mendoza, arriving in Argentina's fourth-largest city on Tuesday evening, 13 December 1994. I then spent four extremely pleasant days in the city prior to the arrival of the other members of the Himalayan Kingdoms' expedition. With its wide tree-lined streets, tiled pavements, and sidewalk cafes, Mendoza was an excellent place to rest and recover from my psephological foray through Europe (studying three elections and two referendums in three months).

I also achieved a personal milestone: when I ran around the circuito lago (i.e., the lakeside circuit) in Mendoza's large Parque Gral. San Martin (or General San Martin Park) for the first time on Wednesday evening, 14 December, it meant that I had run on each of the earth's seven continents. It's not a feat that ranks with Dick Bass' and Frank Wells', but — especially in view of the fact that it includes running the Scott's Hut race in Antarctica — it's an unusual accomplishment nonetheless.

"Not a Prat Among Them" Annette Morris: A exceptionally fit 32-year-old health and safety specialist from Basingstoke, Hants., Annette had been chosen to represent Britain in the short-course triathlon world championships in New Zealand in November, but had decided to go to Aconcagua instead. Cathy Jenkins: The 33-year-old BBC World Service Central European correspondent, Cathy is based in Vienna, but spends a lot of her time covering the war in Bosnia. Don Bolton: At 57, Don was the oldest member of our party. He lives in Guildford, Surrey, and is the director of a computer company. George Hall: A 45-year-old chemical engineer from Bickley, Kent, George was the undoubtedly the most erudite member of our party — his light reading on the mountain was Foucault's Pendulum by Umberto Eco!

John Stibbard: A 40-year-old research scientist with 3M in Harlow, Essex, John was also Cathy Jenkins' partner. Ken Hott: Although he was a member of the "foreign legion" (i.e., not from Britain), Ken — a 32-year-old computer programmer from San Francisco — had recently lived in the UK for more than two years. He is a rock-climber, and had been on previous Himalayan Kingdoms' expeditions. Lyndon Harvey: At 28, Lyndon was the youngest — and fittest — member of the group. Lyndon had trained as a mechanical engineer and worked for Rolls Royce, recently on a two-year stint in China, but he's now based in Manchester. Malcolm Barrett: Although he nominally lives in Harrogate in North Yorkshire, Malcolm lived in Indonesia for many years, and is currently trying to establish an oil company in Kazakhstan. Malcolm was 44 years old, and held the personal altitude record for the group.

Mike Sikora: A 45-year-old computer consultant from Richmond, Surrey, Mike Sikora is a keen cross-country skier and was probably the quietest member of the expedition. His parents were World War II refugees from Poland to Britain, and as a result Mike grew up speaking both Polish and English fluently. Mike Waterworth: One of eight Australians I trekked and climbed with on Lobuje East in Nepal in 1991, Mike Waterworth was 52 years old (making him the second-oldest person in the Aconcagua group). He's a manager/buyer, and lives in Hampton Bay in Victoria. Nigel Roberts: A 50-year-old university lecturer, I'd got to the top of Mt Kilimanjaro on 12 December 1985 and the top of Elbrus on 13 August 1994, and was now attempting to climb my third continental summit. I am, of course, also the author of this web-page. Phil Harmston: A 29-year-old self-employed director of a Bristol-based distribution company, Phil had both a wonderful sense of humour and a grim determination to get to the top — the latter as a result of a pledge not to drink alcohol again unless he reached the summit. Phil's previous high-point was the lowest personal altitude record of the expedition, so there was a real chance he'd remain a teetotaller for the rest of his life...

Tadhg O'Mahony: As his name indicates, 30-year-old Tadhg is Irish. He is a civil engineer, currently working in Britain. Tadhg lives in Lincolnshire and represents the county as a bridge player.

The average age of the 11 men and two women on the expedition was 40 (which was both the mean and median figure). The highest anyone had previously climbed was 6,476 metres / 21,246 feet; the lowest personal altitude record, by way of contrast, was 2,797 metres / 9,176 feet. However, neither these statistics nor the individual pen-portraits of the members of the expedition reveal the amazing amount which we had in common. Eleven of the thirteen of us on the expedition (i.e., all bar John and Phil) had been trekking or climbing in the Himalayas; seven people (Annette, Cathy, John, Lyndon, Malcolm, Mike Sikora, and Mike Waterworth) had been hiking or climbing in the European Alps; and five of us (namely, Annette, Ken, Mike Waterworth, Phil, and I) had been tramping or climbing in New Zealand. With respect to other Seven Summits, five of us (namely, George, Lyndon, Mike Sikora, Tadhg, and I) had climbed Mt Kilimanjaro; three of us (George, Ken, and I) had climbed Mt Elbrus; and three members of the group (Annette, Mike Waterworth, and Phil) had climbed Mt Kosciusko. Perhaps the most staggering coincidence of all was that eight of us had been to just four universities in England — namely, Cambridge (Cathy and George), Essex (Mike Sikora and me), Nottingham (Annette and Malcolm), and Southampton (John and Lyndon). The expedition leader was Simon Lowe, a 34-year-old former major in the British Army. A skilled climber, he had twice been on combined services expeditions to Mt Everest, and had led a highly successful Himalayan Kingdoms' expedition to Aconcagua ten months previously. Simon was an excellent leader. He was authoritative and firm when he had to be. For example, his lectures to us about the dangers of dehydration and altitude sickness were very impressive, and he didn't hesitate to tell people if he thought they were biting off more than they could chew. More often, however, he was relaxed and witty. His stories on topics ranging from hill tribesmen in Aden to French mountaineers on Everest had strong punchlines and everyone in fits of laughter. Daniel Aliesso was our guide. Born and raised in Mendoza, Daniel first climbed Aconcagua in 1984. Ten years later, now aged 30, Daniel has climbed the mountain 20 times (indeed, he's twice held the speed record for the Normal Route by climbing from the Plaza de Mulas Base Camp to the summit in 7 hours and 29 minutes in February 1987, and then climbing it in 6 hours and 42 minutes in January 1990). Daniel and his wife, Maria Marta, have their own trekking and guiding company, and — with respect to British expeditions — work exclusively for Himalayan Kingdoms. Daniel has also climbed two of the world's eight-thousand metre peaks — namely, Cho Oyu (8,153 metres / 26,748 feet) and Shishapangma (8,013 metres / 26,289 feet). The quality of the service Daniel and his staff provided at Base Camp and Daniel's strengths as both a guide and leader were outstanding, and I've told Himalayan Kingdoms that I will unhesitatingly recommend their Aconcagua expeditions to anyone who wants to go there because of the company's links with Daniel. Approaching Aconcagua

The 180 kilometre drive — largely alongside the fast-flowing, muddy-brown waters of the Mendoza River — was through a stark and arid landscape. The higher we rose into the mountains, the bleaker the terrain became.

Puente del Inca is 2,726 metres / 8,943 feet above sea-level and takes its name from a large, natural stone-arch which spans the Mendoza River. The arch is also the site of thermal springs, and as a result some rocks in the area are coated with bright yellow algae, while others — especially beneath the bridge — are covered in white crystals. We spent the night in the Hosteria Puente del Inca (which is where the majority of people setting out for Aconcagua stay).

At eleven o'clock on Tuesday morning, 20 December 1994, we were driven north-west from Puente del Inca for five kilometres or so in the back of a "ute" (or pick-up truck) to the small tent which marks the entrance to the Aconcagua Provincial Park. After taking some group photographs, we set out at 11:40 am to begin the walk-in to Aconcagua.

A few minutes later we came to the Horcones Lake — which is really only a small tarn surrounded by grass, but it affords wonderful views and reflections of the south face of Aconcagua. What a superb start for any expedition!

The walk to the Horcones River and then up the river valley is neither steep nor strenuous, and after less than four-and-a-half hours we reached Confluencia — at the junction of the main branch of the Horcones River (coming down from the northern and western flanks of Aconcagua) and the Little Horcones River (or Horcones Inferior, which flows out of the glacier at the foot of the south face of the mountain). Confluencia is an obvious and popular spot for people wishing to break the 32 kilometre walk up the Horcones valley to Base Camp. The mules carrying our gear had arrived in Confluencia shortly before we did, so we were able to pitch our tents almost immediately (contributing, incidentally, to a community which numbered 21 tents by the end of the day).

At 9:30 the following morning we began an acclimatisation hike up the Little Horcones valley towards Plaza Francia and the south face of Aconcagua. At 12:45 pm we reached the 4,000 metre mark (i.e., 13,123 feet), and stopped for lunch at a spot with a clear view of the south face. Its sheer cliffs towered very nearly 3,000 metres / 10,000 feet above us; they are also about 7 kilometres wide. To put the size of the mountain into perspective, it is important to realise that Aconcagua's south face simply dwarfs one of the world's best known mountain faces — namely, the north face of the Eiger (which is "only" 1,798 metres / 5,900 feet high and "merely" a kilometre or so across). While we gazed at the south face of the mountain, we saw several small avalanches — awesome testimony to the severity of its slopes. After posing in front of the south face for yet another group photograph, we returned to Confluencia (a walk that took only about two-and-a-half hours).

On Thursday, 22 December, we woke at 7:00 am, had breakfast, washed, packed, took our tents down, and set out at 9:10 am on the roughly 20 kilometre walk from Confluencia to Plaza de Mulas, the Base Camp site on the north-western slopes of Aconcagua. By the time we reached the start of the area known as the Horcones River's "wide beach" (which is basically a broad braided-river valley), there was very little vegetation and almost no shade whatsoever, and the walk up the valley to Base Camp was — without doubt — the hottest walk I've ever done in my entire life.

The sun beat down mercilessly on us, and if it wasn't for the wonders of 15+ sun-block, we'd all have been fried to a frazzle. The walk-in took exactly eight hours, and on the "approach march" we generally fell into three groups: a small ultra-fast group consisting of Annette, Cathy, and Lyndon (once again — as on Elbrus — women led the way!); a fairly large group of us were in the middle — viz., Don, George, John, Mike Sikora, Tadhg, and me; and then there was the slow section of our party — namely, Ken, Malcolm, Mike Waterworth, and Phil. I couldn't help recording these groups and the names of the people in them in my diary and wondering whether they were a portent of things to come ...

Plaza de Mulas (i.e., the Place of the Mules) is well-named. It's the end of the line for the mule trains which are used to ferry equipment up and down the Horcones valley. Mules put sherpas and yaks to shame: they move extremely quickly and do the 80 kilometre round-trip from Puente del Inca to Base Camp and back in a day. Plaza de Mulas resembles a small village — for good reason: at the height of summer, there can, apparently, be about 200 people at Base Camp. While we were there, I'd estimate that there were between 80 and 120 people in the camp on any one night, and the place was a Babel of languages — Spanish, English, French, Japanese, and Portuguese were among the most common. Plaza de Mulas is also 4,230 metres / 13,878 feet above sea-level. The altitude — or was it the heat or the exertion? — was beginning to tell. Cathy was violently ill immediately after we arrived at Base Camp, and Simon's talk to us in the mess tent after dinner that evening about the dangers of altitude sickness — especially pulmonary and cerebral oedema — was certainly timely! So too was the the fact that the next day — Friday, 23 December — was a "rest day." After a late breakfast (which began at 9:30 am, just as the sun peeked over the western face of Aconcagua and finally hit the campsite) and after one-and-a-half hours' "personal administration" (mainly devoted to washing clothes in a tiny, icy stream near the camp), we all walked over to the hotel, about half an hour's walk across the moraine at the foot of the Horcones glacier. The hotel was well built and clean — a far cry from the Priut on Elbrus, for example, but there were very few guests staying in it. There were very few staff for that matter, and no-one objected to the vigorous game of table tennis various members of our party played — with Cathy (now obviously better) and Tadhg rapidly establishing themselves as our ping-pong champions.

During the afternoon, Simon accompanied nine of us to the nearby Horcones glacier where we sharpened our cramponing and ice-climbing skills. Eight of us — Annette, Don, John, Ken, Lyndon, Mike Waterworth, Phil, and I — had signed up to climb the mountain via the Polish Glacier (on the eastern side of Aconcagua), while Tadhg — who'd opted to climb the la ruta normal (i.e., the Normal Route) — came along as well in order to try out the plastic climbing boots he'd bought in England on the day that he left Heathrow for Argentina. The others members of the Normal Route party — Cathy, George, Malcolm, and Mike Sikora — gallantly stayed behind at Base Camp to fill the expedition's two large water barrels.

Cache and Carry

We zig-zagged slowly back and forth up the scree; but the climb wasn't particularly difficult, and even with two rest stops it took only two-and-a-half hours to reach Canada Place. We dumped our Camp I supplies there, and then spent a very pleasant hour sheltering from the wind and having lunch.

The descent back to Base Camp was even more pleasant: most of us simply ran down the most direct route possible on the scree, and we were back at Plaza de Mulas in an hour. Everyone bar Malcolm fared well: it was his turn to be sick.

Dinner was earlier than usual (it was served at about 7:20 pm rather than 8:00 pm). Both because Annette was keen to open the Christmas presents she's brought up to Base Camp in her gear and because it was already Christmas Day in Australia and New Zealand (obviously any excuse would do), dinner became the main focus for our Christmas celebrations. Champagne, Christmas cake, and cognac, as well as Annette's presents (which included a musical card from her mother and sisters, and a book from her boyfriend listing 101 things not to say during sex), Mike Waterworth's set of six miniature Santas, and a Christmas card for me from Heather and Evan illustrating the Twelve Days of Christmas (the words of which had eluded us during the walk-in from Confluencia to Base Camp) all contributed to a exceptionally pleasant evening. Speaking personally, it was the calm before the storm...

Sunday, 25 December 1994, was the worst Christmas I've ever had. I felt slightly queasy before breakfast, and although I ate my food (toasted cake and jam, toast and scrambled egg), I didn't enjoy it. We left Base Camp at 10:05 am, carrying very heavy packs containing cold weather and survival gear for the day, snow and ice climbing equipment (which we would need, especially for the Polish Glacier), and food and fuel for Camps II and III. For the first two hours or so, I was ok; but then — just before we reached the 5,000 metre mark (i.e., 16,404 feet) — I began to struggle. When we reached the top of the steep scree slope which had formed our horizon for a long time, an area known as the cambio de pendiente (in other words, the change of slope), I was more "knackered" than I'd ever been before on any previous mountaineering expedition. I collapsed, exhausted and close to tears, alongside the rest of the party, sheltering from the wind behind a low stone wall. I managed — with considerable difficulty — to get some food inside me, and it made me feel a bit better. I also crossed a personal Rubicon. Having conducted both an internal and an external debate (the latter with Phil) during the morning about whether or not I'd persist with my plans to attempt to climb Aconcagua via the Polish Glacier route, I knew I'd have no chance of success on the Polish Glacier and that if I were to ever see the summit of Aconcagua it would be via the Normal Route.

Simon encouraged me to try to go on to Nido de Condores (i.e., Condors' Nest) — the site of our second camp. He redistributed a lot of the equipment I was ferrying up the mountain to other members of our party — who were already carrying extra gear as a result of the fact that Don had suffered dizzy spells around about the 5,000 metre mark and had thus turned round and headed back down to Base Camp. As a result, I wasn't the only exhausted person when we reached Condors' Nest at 3:35 pm (that is, exactly five-and-half hours after leaving Base Camp): everyone bar Lyndon was exhausted — even Annette!

After Daniel, Lyndon, and Simon had packed and cached the gear for Camp II, we left Nido de Condores at 4:20 pm and set out to return to Plaza de Mulas. All went well for an hour or so, until — somewhere below Canada Place — I paused for a drink of water, then leant over the side of the path and spewed my guts out! Of course, being sick made me feel better for a while, and I reached Base Camp at 6:16 pm without further ado. I lay down — exhausted and nauseous — in the tent Mike Waterworth and I were sharing. I didn't go to dinner at 8:00 pm. At about 8:20 pm I was violently ill again. Consequently, Daniel and Simon summoned the doctor to see me. (Plaza de Mulas is so big that a doctor and a paramedic are stationed there throughout the summer.) Exhaustive tests — blood pressure, pulse rate, chest, heart, and stomach — convinced the doctors, and me, that there was probably nothing too seriously wrong, and after taking an anti-nausea pill and having some warm fruit juice, I had a reasonably good night's sleep. The next day — Boxing Day — was, thankfully, a rest day. Feeling weak but not ill, I had breakfast, during which I thanked everyone for the help they'd given me on Christmas Day, and also announced my decision not to climb the Polish Glacier. Don said that he, too, was now a candidate for the Normal Route. The Polish Glacier : Normal Route ratio had changed from 8 : 5 to 6 : 7. A wonderfully indolent morning was capped by a gloriously hot shower under a water-bladder rigged up in the mess tent.

I ate a hearty lunch, and at 4:10 pm went to the doctors' tent. They tested my blood pressure again and pronounced it perfecto. I noted in my diary that although I thought I had "a less than even chance" of reaching the summit, at the same time I also thought that "I could manage a very strenuous eight hours on summit day." The rest of the afternoon was spent sorting out gear in preparation for our move out of Base Camp and up the mountain. At dinner, Mike Waterworth announced that he, too, was now a candidate for the Normal Route. We hadn't really hit the slopes of Aconcagua (we'd not yet slept higher than Plaza de Mulas) and the Polish Glacier : Normal Route ratio had been completely reversed. It had changed from 8 : 5 to 5 : 8. The Final Push Considering the circumstances, Mike very gamely volunteered to sling a dozen odd cameras round his neck and take group photographs of us before we left Plaza de Mulas at 12:30 pm and set off up the scree slopes towards Canada Place for the third and final time. We were carrying very full rucksacks — in addition to our normal cold weather gear and equipment, we now had to carry our sleeping bags and thermarest sleeping mats, and each of us had a portion of a tent as well. During the climb, Phil let it be known that he was also joining the Normal Route group. As a result of Phil's switch and Mike Waterworth's departure, the Polish Glacier : Normal Route ratio now stood at 4 : 8.

I was delighted by the fact that the three-hour trek from Base Camp to Camp I was the complete opposite of my experience on Christmas Day. I didn't find any of the three stages of the climb too strenuous, and at Canada Place wrote in my diary that although "I'm never overly optimistic, ... today's climb ... augurs well for the future." Of course, one factor we had no control over whatsoever was the weather. During our first week on the mountain — from Tuesday, 20 December, through to Tuesday, 27 December — we had been blessed by amazingly good weather. Brilliant, hot sunny days were always succeeded by cold, clear nights with a profusion of stars. The question was, would it last?

Part of the answer, at least, was provided during the night. We were buffeted by strong gusts of wind and the tents flapped ceaselessly. In the morning we lay in our sleeping bags for as long as possible waiting for the sun to hit the camp (it did, eventually, at 9:00 am) and for the wind to die down (it didn't). After we'd had breakfast and repacked, in an attempt to slow everyone down Simon asked me to take the lead; and at 11:40 am I set off from Canada Place towards Condors' Nest. It didn't work: feeling the pressure of fast, fit climbers like Annette, Cathy, and Lyndon behind me, I walked more quickly than I would have liked and was quite tired when — after only half an hour — I called a halt just above the 5,000 metre mark. I didn't make the same mistake twice, and afterwards I hung back and kept pace with some of the slower climbers like Don, George, Malcolm, and Phil. (It's worth noting, incidentally, that Annette and Lyndon were part of the Polish Glacier group; while Don, George, Malcolm, and Phil were all Normal people!) When we reached the change of slope, the spot where I'd nearly fainted with exhaustion three days earlier, I was feeling fine — so much so that that I asked Tadhg to take a photo of me at the cambio de pendiente before I even put my rucksack down. The last part of the climb to Condors' Nest took about an hour, and we arrived at Camp II at 2:25 pm (in other words, the climb from Camp I to Camp II had taken exactly two-and-three-quarter hours).

Condors' Nest is 5,334 metres / 17,500 feet above sea-level; and after we'd put up our tents, the climb and the altitude took their toll: I lay down in the tent and fell fast asleep. Ken, concerned for my welfare, opened my rucksack, got out my thermarest, inflated it, and brought it in to me. Saints obviously exist, and heaven clearly begins at 5,334 metres! Lunch was at 4:50 pm and was scrumptious — it included tinned artichokes and sardines. Dinner was served three hours later, and when the sun disappeared behind some low-level Chilean haze at 9:00 pm it quickly got very cold, so we all beat a hasty retreat to bed. The night was, once again, very windy.

Thursday, 29 December, was Heather's and my 28th wedding anniversary, so it was doubly nice to have it as rest day. Well, some of us did. Despite the fact that Annette, Ken, and Lyndon all had headaches, the Polish Glacier group — which we'd nicknamed the PGVs: the Polish Glacier Victims! — set off at 11:15 am with Simon and Sebastian, an assistant guide who'd arrived at Camp II the previous day to help the Polish Glacier group, to ferry equipment to the glacier for their climb. The Normal people, on the other hand, left at 11:30 and merely walked across to El Manso, a 5,340 metres / 17,519 feet high ridge-like peak, a short distance from the camp site, and back. It was an extremely pleasant one-and-a-half hour trip with excellent views back down to Canada Place, up to the summit of Aconcagua, and across to two other impressive Argentinean peaks (namely, Mercedario, 6,770 metres / 22,211 feet, and La Mesa, i.e., The Table, which is about 6,500 metres / 21,345 feet high).

On our return to our tents, I sat in the sun and wrote a frank assessment of both the condition I was in and my chances of climbing Aconcagua. It's worth recording in full:

The PGVs returned to Condors' Nest at 5:30 pm. They'd carried their gear to a spot at about 5,600 metres / 18,372 feet high, at the edge of the glacier, and had found a feasible route up the glacier, but the day had left them all — apart from the ever-effervescent Lyndon — exhausted. They were "whacked." Hopefully, though, that was just temporary, and hopefully the huge bank of clouds which built up in the evening to the north of the mountain was just temporary too.

When we got up on Friday morning, 30 December, our hopes had materialised. All the members of the Polish Glacier group were in good heart, and the menacing cumulo-nimbus clouds had disappeared entirely. After breakfast, we all re-sorted our gear in preparation for the final push to the summit (as well as to enable us to leave quite a lot of equipment stashed at Condors' Nest). At 11:30 am, Annette, John, Ken, Lyndon, and Simon set off for the Polish Glacier; and fifteen minutes later (after taking a Normal Route group photograph — i.e., of Cathy, Don, George, Malcolm, Mike Sikora, Phil, Tadhg, and myself), we started to climb up towards our third camp site.

We were led by Daniel and accompanied by Victor (a tall black-bearded assistant guide, who'd joined us at Canada Place, and looked just like a pirate when he wore a scarf to keep the sun off his head!). We zig-zagged slowly back and forth over scree that was a rainbow of different pigments. The scree was usually a light dusty brown, occasionally it was gleaming white, sometimes it was bright yellow (from sulphur deposits: evidence of Aconcagua's volcanic past), and every now and then there were even patches of purple scree. We'd been told it would take about three hours to reach the Berlin Huts, where we'd be erecting Camp III, but were very pleasantly surprised to find that the walk up to the Huts took only just over two hours and, what's more, we all arrived in very good shape. When we reached the Berlin Huts (which are 5,800 metres / 19,028 feet above sea-level, almost the height of Mt Kilimanjaro), I deliberately asked Tadhg to take a photo of me while I still had my rucksack on — so that I can disprove Heather's gibe that all my mountaineering is packless, done with the aid of porters or yaks! The three huts at Berlin — Berlin, Libertad, and Plantamura — are unusable, wind and avalanches have rendered them useless; but the site is a popular spot for camping prior to tackling the summit of Aconcagua, and by the end of the day there were 14 tents in the vicinity of the huts (making an overnight population, I'd guess, of about 35 people).

The wind had died down, and — as a result — pitching our tents was easy (Ken, Phil, and I had shared a tent at Camps I and II, but when Ken went off to the Polish Glacier, Phil and I became the only two-tent team in the Normal Route group, a luxury literally worth the weight of carrying a tent between two, rather than three, people). The afternoon was quiet and restful. Radio schedules before lunch and after dinner brought two interesting pieces of news. First we learnt that Mike Waterworth had reached Mendoza safely, and after a series of checks in the Italian Hospital (probably the best hospital in Mendoza) had found nothing seriously wrong, he'd been allowed to check out of hospital and back into the Plaza Hotel. The second radio "sched" revealed that Simon and the PGVs had had an exceptionally hard day, that they were all extremely tired, and that they had, therefore, decided to have a rest day before making their summit attempt on 1 January, a day later than initially planned.

For our part, though, the Normal Route group was able to keep to its original agenda. I slept with almost all my clothes on, and also shared my sleeping bag with my water bottles, inner-boots, and camera (to stop them freezing during the night). Daniel woke us just before my alarm went off at 4:50 on Saturday morning, 31 December — the last day of the year. We had breakfast at 5:15 am (oats and tea: it wasn't very appetising, but at least I could eat it and didn't feel sick), and set off — almost as planned — just after six o'clock.

It wasn't very dark (I had my head-torch on for only 10 minutes or so); it wasn't very warm (the temperature in the tent when we got up was -5 degrees C); and it wasn't very windy. Reviewing the climb later, few of us could recall much about the first part of the day's slog. Zombie-like we made our way up to Independencia (yet another ruined shelter, this one at 6,250 metres / 20,505 feet above sea-level). We had a long rest in the sun.

Cathy's feet were frozen — the circulation in her toes restricted by too many socks, but she solved the problem by taking off one pair and with the aid of some "hot rocks" which a French climber kindly gave her to put into her boots. At Independencia, I felt very tired and strongly doubted my ability to reach the summit. However, I consoled myself with the thought that at least I was well above the magical 6,000 metre / 20,000 foot mark — a goal I'd wanted to achieve ever since I climbed Mt Kilimanjaro (which is a few frustrating metres short of six thousand). Just before we left Independencia, Daniel pointed out the route ahead — up a short slope, through a patch of snow, and onto a ridge called Windy Col. The col is exceptionally well-named. As we reached the crest of the ridge, we were hit by gale-force winds and the temperature dropped sharply. We made our way slowly across a long traverse (I'd estimate it to be about a kilometre in length), pausing only briefly behind a large rock in a vain attempt to shelter from the wind, all the time aiming for the steep scree slopes at the foot of the final 400 metre high bulge that forms the summit of the mountain. Before we completed the traverse, however, Tadhg and I were forced to stop again. The wind-chill factor meant that the air temperature was equivalent to about -25 degrees C, and both of us had frozen fingers, even though I'd put "hot rocks" (which Greg Matte — despite the fact that, or because, he'd called me a bastard? — had sent to me from America) in my gloves. Daniel instructed us to hang our arms down below our waists and to clench our hands rapidly open and shut. Slowly the blood began to flow again in my fingers. Oh, how it hurt! My eyes filled with tears, but Daniel was unsympathetic. "Yes," he said, "You cry. The pain means you can feel again. You will be all right."

From then on, however, things looked up — literally. After sitting in the sun at the far end (that is, the western end) of the traverse and eating and drinking, I began climbing again at 9:30 am, making my way up the final scree slopes on the northern side of Aconcagua. The area is known as the Canaleta (an adaptation from the Spanish word for channel), and it has a fearsome reputation for defeating climbers. In Aconcagua: The Stone Sentinel, Thomas Taplin bluntly notes that "the dreaded Canaleta is horrific enough to not only completely negate the relatively good trail conditions and scenery which precede it, but push one to the brink of mental defeat as well." It is often said that when climbing scree slopes on mountains like Kilimanjaro and Ngauruhoe, it's a case of one step forward and two steps back. That's a considerable exaggeration, of course, but I have to admit it's very nearly true when describing the final haul up the scree through the Canaleta. For a start, the scree is far larger than on any other volcano I've ever climbed. Large rocks the size of day-packs or buckets sit on top of smaller stones, which in turn cover loose pebbles and sand. The angle of the slope is around 40 degrees, and the unstable nature of the surface means that not even generations of climbers have been able to carve a clear set of firm zig-zags (or switchbacks) up the final section of the Normal Route on Aconcagua. Two quotes from books about Aconcagua encapsulate the problems of climbing the Canaleta. In Thomas Taplin's book, Craig Roland (one of the four successful summiteers in Taplin's group) notes that "the footing in the Canaleta was very unstable with slippy-slidey, rolling rocks. We had to constantly focus, not just on getting up, but on finding stable rocks. The rocks, however, were never quite big enough to be stable." And in their book, Aconcagua: The Sentinel of Stone, Alejandro Randis and Maria Marta Lavoisier simply say that "the Canaleta has big unstable stones." And yet the very nature of the scree forced me to make far faster than expected progress. It was the mountaineering equivalent of New Hampshire's state motto: "Live free or die." If you didn't take substantial steps, find firm footholds, and actually ascend, you slipped back and literally lost ground. The final section of the Canaleta is a notorious funnel of scree which swings left, or eastwards, up through a canyon-like gap in the rocks to the edge of the Guanaco Ridge (which separates the north and south summits of Aconcagua) and then onto the final summit knoll itself. We all paused for a long rest before tackling it, and Daniel told us that Don had once again experienced dizzy spells, as well as a partial loss of sight, and that he had therefore turned round and — accompanied by Victor — headed back down the mountain (aiming first for Camp III, but, if necessary, he would go right down to Base Camp). As the only guide for seven of us, Daniel said that he would remain at the rear of the party and that for the rest of the way we should climb at our own pace. That suited me perfectly. I set myself a series of targets — an outcrop of black rocks, a snow patch, and an overhanging rock just below the summit, and I made my way steadily towards them. When I reached my goal, I deliberately stopped for a long rest. At each stop I ate one of the Tracker muesli bars I'd bought in England and several of the Dextrosol glucose tablets I'd got in Denmark (and had previously found very helpful in both Nepal and Russia). I also had a substantial drink of water (though this latter task got harder each time — despite being in my rucksack, the water in the three water bottles I was carrying got more and more frozen throughout the day, so not only was there less water for me to drink each time I stopped, but the ice that was forming round the inside-rim of the bottles made it more and more difficult to drink the water that was there). Then, when I was rested and refuelled, I would begin to make my way slowly to my next marker. It was a technique that worked and I steadfastly refused to alter it, even when I approached my last resting spot and could see Cathy waving to me from the summit and encouraging me to join her and Phil at the top. I was determined to reach the top with enough energy both to appreciate my time on the summit and to get down relatively painlessly. (I vividly recalled how I'd nearly collapsed at the saddle after descending from the summit of Mt Elbrus, and it was an experience I didn't want to repeat.)

After scrambling up some rocks at the eastern end of the summit ridge (and, in the process, missing Cathy and Phil, who went down another route), I reached the summit of Aconcagua at 1:43 pm. The climb from Camp III had taken me just under seven-and-three-quarter hours; well under the ten Daniel was prepared to allow us (he'd told us that if we weren't at the top by 4:00 pm, we'd have to turn back). Even though it was more than a thousand metres higher — or just over 3,500 feet higher — than I'd ever been before, I felt fine. I spent an hour on the summit, far longer than I'd ever spent at the top of any other major mountain.

I took all the photographs I planned to take (including a 360 degree series of shots with the special panorama camera I'd forgotten to take to the summit of Elbrus!), and I had no trouble whatsoever breathing or thinking. My first thought, though, on reaching the summit was, "Thank heavens I've reached the top. I won't have to come back here again!" Aconcagua is not a magical mountain like Kilimanjaro, and it doesn't have the splendid symmetry of Elbrus. It's been called "an intolerably monotonous slag-pile" in James Ramsey Ullman's classic account of The Age of Mountaineering and — sadly — I have to agree that that's a reasonably accurate description of the Normal Route on the mountain. Malcolm reached the summit about ten minutes after I did — and he was one reason why I spent so long on the top. He was utterly exhausted. He was muttering, "I should have turned back" and seemed to be foaming at the mouth (in reality, he was probably suffering from moderate dehydration, like a runner at the end of a race). He lay down, and I forced him to eat and drink. Shortly after George reached the summit, Malcolm said he wanted to go down, to be out of the wind. As the wind was whipping into the north face of the mountain but was — at the same time — comparatively light at the summit, I tried to persuade him to stay on the top, rather than go down into the full force of the wind. George disagreed with me, so I then helped Malcolm clamber down to a path below the summit knoll. Daniel saw us and climbed up to us as quickly as he could. After catching his breath, Daniel's psychology was marvellous. Before he even asked Malcolm how he felt, he congratulated him on reaching the summit. One could almost see Malcolm recover his self-esteem, if not his strength! After ascertaining that Malcolm would be all right and instructing him not to move away from the spot, Daniel and I headed back up to the summit. (It didn't occur to me at the time, but can I now claim to have climbed Aconcagua twice? I even have two photographs to prove it: one of me by myself at the summit on the first occasion; the other taken together with Daniel!) A short while later both Tadhg and then Mike Sikora made it to the summit as well. In Mike's case, it was a triumph of determination over adversity. His ski-poles had broken while we were on the traverse across to the start of the Canaleta; and walking behind him at that stage of the climb, watching him drag his poles uselessly behind him, I thought he had little or no show of reaching the summit.

A Decent Descent

I continued to have deliberate refuelling stops on the way down, but after only two-and-three-quarter hours (that is, at 5:30 pm) I was back at Camp III. Cathy and Phil were already there, and after chatting to Phil for a while, we both took off some of our clothes, climbed into our tent, and — despite the very strong winds which battered the tent ceaselessly — both fell fast asleep. At about 8:30 pm Daniel brought some hot soup for us to the tent, but it wasn't long before we were asleep again. A few minutes before midnight, I got up for a pee. As I walked back to the tent, I looked at my watch: it was just about to turn 12. I paused under a cloudless sky bright with stars, and welcomed in the New Year. Although I had a great deal to celebrate, it wasn't much of a party. The only sound was the ceaseless howling of the wind in the cliffs above our camp site.

We all slept well — long and late. The wind was so ferocious that Daniel brought us breakfast in bed. He also brought us news of the Polish Glacier group. The wind had forced them to abandon their summit attempt via the Polish Glacier, and they had set out instead for Independencia and the Normal Route. As the wind had forced many of the people who'd set out at about six in the morning from Camp III for the summit to turn round and come back, we could only hold thumbs for the Polish Glacier group. Would they really be PGVs? Despite the wind, we eventually managed to take the tents down and repack, and finally left the Berlin Huts area at 12:25 pm and headed down to Condors' Nest, which we reached in just three-quarters of an hour. We collected the gear we'd left at Condors' Nest, redistributed it, and half an hour later — at 1:40 pm — left what had been Camp II. Below the change of slope, most of us stopped to rest at the rocks which form the 5,000 metre mark. As I took a picture of the group, using the last film on my wide-angle panorama camera, I pondered the question, "When will l next climb above the 5,000 metre mark?"[2]

Afterwards, I had a second wind. Like a horse that knows it's in the home straight, I strode out for Base Camp, and at 3:30 pm was the first to arrive there. Despite an exceptionally heavy pack (everything that goes up must come down!), it'd had taken me less than two hours to get back to Plaza de Mulas from Condors' Next. This had two advantages: I was able to avoid walking in anyone else's dust, and I was also able to take candid photographs of everyone else as they arrived back at Base Camp. In the evening, before dinner, we heard about the PGVs. Ken had dropped out, exhausted, before reaching Independencia, but the rest of the group had struggled on up the Normal Route against the wind to reach the summit. As Malcolm noted, Daniel's success rate of 80 per cent was almost spot on. Ten of the thirteen of us had got to to the top — only Mike Waterworth, Don, and Ken hadn't. (That's a success rate of 76.9 per cent, and closer to eighty per cent than 11 out 13 — i.e., 84.6 per cent — would have been.) Monday, 2 January, was a rest day for the eight of us in the Normal Route group. I didn't leave Base Camp at all — content simply to re-sort my gear, write my diary, read, and take photos of the PGVs as they came down off the mountain. Utterly unsurprisingly, Lyndon was the first one back (at 5:30 pm) — I gave him with a can of Coke, a present from the oldest summiteer to the youngest! John was next; and Annette and Ken, accompanied by Simon, arrived just before 7:00 pm. They were exhausted: the mountain had almost managed to defeat even Annette, who'd been sick at their Polish Glacier camp site, and could barely remember her time on the summit. They recovered quickly, though, and that evening everyone enjoyed our celebration dinner, which included champagne, as well as cognac I'd bought at Heathrow.

Although we'd set 10 o'clock the next morning as our departure time, it was lucky that we weren't ready then and that we were, instead, still busy packing up and taking tents down. I heard Phil scream, "Rock!", and looked up to see a huge boulder — the size of a small car — hurtling down the cliffs above Plaza de Mulas. It hit the ground near the spot where we'd collected water from melting snow and broke into football-size pieces, which flew like shrapnel across the main path through Base Camp. Several tents belonging to a Chinese expedition were shredded, but — miraculously — no one was injured. It could have been a very different story, though, had we been ready on time and just setting out along the main path out of the camp. The walk out from Plaza de Mulas to the park entrance is about 32 kilometres (or 20 miles) long. Once again, the wide beach area of the Horcones valley was hot, arid, and dusty, but the facts that we were, after all, heading downhill and that we had a cool tail wind almost through to Confluencia made the trip easier and far quicker than the walk-in.

At 5:30 pm — exactly seven hours after we left Base Camp — six of us (Annette, Cathy, Don, Lyndon, Tadhg, and I) reached the park entrance together. Daniel had arrived a few minutes before us, and the seven of us promptly climbed into the "ute" that was waiting for us. We'd been in the park for a fortnight, and were ready — highly ready — for the beers and showers beckoning us to civilisation. However, a comedy of errors stemming from the fact that no-one rang the "ute" owner when the rest of our party arrived at the park entrance, meant that we had to cool our heels in Puente del Inca for almost two hours before we were taken another five kilometres down the road to the Hosteria at the Los Penitentes ski-field, and were finally able to start the process of removing Aconcagua's dust and dirt from our bodies ...

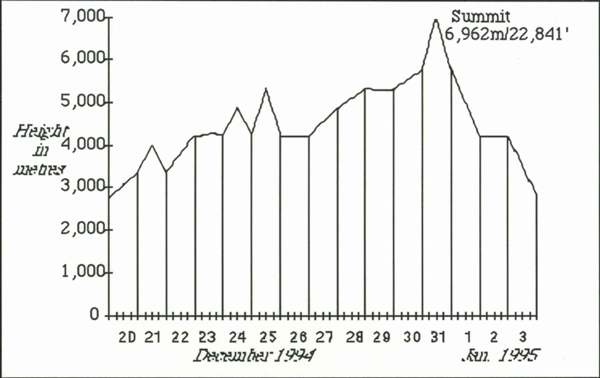

The following diagram summarises what we'd done during the previous fortnight. It charts our height gains and losses on a daily basis while we were in the Aconcagua Provincial Park. In doing so, it illustrates one of the reasons why we were so well acclimatised. During the first week, we frequently climbed high and slept low. That's the best formula I know for combating altitude sickness.

After Aconcagua We'd come down off the mountain a day ahead of schedule, which meant that we had two full days to enjoy the delights of the city. We did. We had some superb meals in Mendoza's sidewalk cafes and restaurants; Annette and I went running in San Martin Park; we swam in the hotel's swimming pool; we visited the Trapiche winery and tasted some of its products; and I had both my pairs of leather boots professionally cleaned by a streetside vendor for the princely sum of five dollars.

On Friday evening, 6 January, we all flew on Austral Airlines from Mendoza to Buenos Aires and checked into the Principado Hotel, close to the centre of the city. Early the next morning, three of us — the two Mikes and I — flew to Iguazú. Mike Sikora had arranged and paid for the trip before he left England; so, for the sake of convenience, Mike Waterworth and I dovetailed our plans for visiting the Falls in with his, and the three of us were thus able to be accommodated in one room in the Hotel Internacional Iguazú for a mere $88 more than Mike had originally paid. I'd been to the Victoria Falls three times (in 1953, 1957, and 1960) and to the Niagara Falls once (in 1988), and thus desperately wanted to see the third member of the holy trinity of grand waterfalls. At the same time, though, I suspected that I'd find the Iguazú Falls inferior in comparison to the Victoria Falls. I was wrong. The Iguazú Falls are simply stunning.

The raw power of the orange-brown water flowing through the jungle and over the 72 metre high (236 foot high) cataracts on the Paraná River is breath-takingly beautiful. Mike Sikora, Mike Waterworth, and I spent hours wandering along the paths and walkways that have been constructed to give visitors clear views of the Falls. We also crossed over to Isla San Martin (San Martin Island) for spectacular close-up scenes of both the Argentinean and Brazilian Falls. The heat (32 degrees C), the humidity (allegedly 100 per cent), the jungle, and the birds (including parrots, toucans, and vultures) added to the atmosphere. Indeed, I was so enchanted by Iguazú that I got up before six the next morning to see the Falls at sunrise. The scene was unforgettable; the brown water infused with a golden spray.

We flew back to Buenos Aires on Sunday morning, 8 January, and Mike Sikora and I had time for a quick tour of some of the sights of the city with Mike Waterworth as our guide. For me, the highlights were seeing the Casa Rosada (the pink presidential palace in Plaza de Mayo) and Eva Peron's mausoleum in the Recoleta cemetery (which wasn't difficult to find — there was a group of American exchange students standing in front of it singing "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina"!).

We caught a taxi back to the Principado Hotel, and after a final group photograph on the pavement opposite the hotel (we were undoubtedly a group with something of a passion for group photographs), ten brave Aconcagua expeditioners — Annette, Cathy, Don, George, John, Lyndon, Malcolm, Mike Sikora, Phil, and Tadhg — and our intrepid leader, Simon, were last seen at 3:45 pm in a green mini-bus heading for the airport. Later that afternoon, Ken, Mike Waterworth, and I went off to a cafe on San Martin Plaza for few final cervezas before Ken, too, took off for the airport. The following morning — Monday, 9 January 1995— it my turn to head for home. After five-and-a-half months on the road, I was really looking forward to returning to New Zealand. My entire time away, though, had been marvellous. My academic work — studying elections and referendums in Scandinavia and Germany — had been exceptionally interesting; I'd had two tremendous weeks in Russia climbing Mt Elbrus, seeing Moscow and St Petersburg, and making new friends; visiting other friends as well as relatives in Europe was also an especially enjoyable experience; and — to cap it all off — I had four wonderful weeks in Argentina, during which Aconcagua was literally and metaphorically a high-point. Post-script

Bibliography Dick Bass and Frank Wells with Frank Ridgeway, Seven Summits (London: Pan, no date), 336 pp. — especially Chapters 3 and 6. William Broyles, "Climbing Aconcagua"[Journal, volume number, and date unknown], pp. 149-168. Roger Marshall, "Malevolent Mountain", Equinox, volume 1, number 3, May-June 1982, pp. 28(?)-40. Alejandro Randis and Maria Marta Lavoisier, Aconcagua: El Centinela de Piedra / Aconcagua: The Sentinel of Stone (Mendoza, Argentina: Zeta Editores, 1991), 150 pp. Thomas Taplin, Aconcagua: The Stone Sentinel (Santa Monica, California: Eli Ely Publishers, 1992), 236 pp. James Ramsey Ullman, The Age of Mountaineering (London: Collins, 1956), pp. 154-160. Endnotes [2] The answer to this question turned out to be 2 July 1997, when I was climbing Mt McKinley/Denali. I stayed above the 5,000-metre mark for five days on that occasion, but I haven't been that high again and — in view of my current climbing goals — I very much doubt that I'll do so in the future. ********** |

||

l

l